February 16, 2021

Judgment of the European Court of Human Rights In the case of Georgia vs. Russia

By: Dr Peter Leuprecht

On 21 January 2021, the European Court of Human Rights delivered a judgment in the case of Georgia vs. Russia. Georgia had lodged an application in the context of the armed conflict that occurred between Georgia and the Russian Federation in August 2008. It thus took the Court 12 years to come to a judgment – another example of the excessive length of proceedings before the Court.

On 21 January 2021, the European Court of Human Rights delivered a judgment in the case of Georgia vs. Russia. Georgia had lodged an application in the context of the armed conflict that occurred between Georgia and the Russian Federation in August 2008. It thus took the Court 12 years to come to a judgment – another example of the excessive length of proceedings before the Court.

The judgment was delivered by a Grand Chamber composed of 17 judges and chaired by Robert Spano, the President of the Court. The Court had written evidence from:

- the Independent International Fact-Finding Mission on the Conflict in Georgia established by decision of the Council of the European Union,

- the Office of Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) of OSCE,

- the Commissioner for Human Rights of the Council of Europe,

- Amnesty International,

- Human Rights Watch,

- The International Crisis Group and

- Georgian non-governmental organizations.

It heard 33 witnesses, 15 called by the Government of Georgia, 12 by the Government of the Russian Federation and 6 directly by the Court.

An “administrative practice” of severe human rights violations

In its judgment, the Court distinguishes between the active phase of hostilities during the 5 day war after the intervention by the Russian armed forces (8-12 August 2008) and the occupation phase after the cessation of hostilities (ceasefire agreement of 12 August 2008).

According to Art. 1 of the European Convention on Human Rights, "the High Contracting Parties shall secure to everyone in their jurisdiction the rights and freedoms defined in Section I of the Convention". In the opinion of the Court, the concept of jurisdiction is not restricted to the national territory of a Contracting State. In the case of Loizidou vs. Turkey (Judgment of 23 March 1995, paragraph 62) the Court stated: "Bearing in mind the object and purpose of the Convention, the responsibility of a Contracting Party may also arise when as a consequence of military action - whether lawful of unlawful - it exercises effective control of an area outside its national territory.”

By 11 votes to 6, the Court held that the events during the active phase of hostilities did not fall within the jurisdiction of the Russian Federation for the purposes of Art. 1 and declared this part of the application inadmissible. As far as the occupation phase was concerned, the Court held, by 16 votes to 1, that the events occurring after the cessation of hostilities had fallen within the jurisdiction of the Russian Federation. In the Court’s opinion, the Russian Federation exercised effective control over South Ossetia, Abkhazia and the “buffer zone” from 12 August to 10 October 2008, the date of the official withdrawal of Russian troops, and even after that period there was continued effective control over South Ossetia and Abkhazia. There was a systematic campaign of burning and looting of homes in Georgian villages in South Ossetia and in the “buffer zone”. That campaign was accompanied by abuses perpetrated against civilians and, in particular, summary executions. The Court concludes beyond reasonable doubt that there was an administrative practice contrary to Articles 2 (right to life), 3 (prohibition of torture and inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment) and 8 (right to respect for home) and Art. 1 of Protocol No. 1 to the Convention (peaceful enjoyment of possessions). To find an administrative practice of violations, the Court has regard to two criteria: the repetition of the acts concerned, and official tolerance of them.

A number of mostly elderly Georgian civilians (around 160, of whom one third were women) were detained by South Ossetian forces, under the effective control of the Russian Federation (para. 214), between 10 and 27 August 2008. According to the Court, there was an administrative practice contrary to Art. 3 of the Convention as regards the conditions of detention and the humiliating acts to which they were exposed and an administrative practice contrary to Art. 5 (right to liberty and security) as regards the arbitrary detention of Georgian civilians in August 2008.

There was also an administrative practice contrary to Art. 3 of the Convention as regards the acts of torture of which the Georgian prisoners of war were victims.

The Court found that there was an administrative practice contrary to Art. 2 of Protocol No. 4 to the Convention (right to liberty of movement) as regards the inability of Georgian nationals to return to their homes.

The Court also held that the Russian Federation had a procedural obligation under Art. 2 of the Convention to carry out an adequate and effective investigation into the events. However, “the investigations carried out by the Russian authorities were neither prompt nor effective nor independent” (para. 336). There was therefore a violation of Art. 2 of the Convention in its procedural aspect.

Finally, the Court found that the Russian Government had fallen short of their obligation to furnish all necessary facilities to the Court in its task of establishing the facts of the case, as required by Art. 38 of the Convention. In particular, the Russian Government had refused to submit “combat reports”, on the grounds that the documents in question constituted a “State secret”.

The findings of the Court reveal a number of severe violations of human rights and indeed an administrative practice of violation.

The Court held that the question of the application of Art. 41 (just satisfaction) was not ready for decision and consequently reserved it in full.

The Court divided on a fundamental issue

All but one of the findings of the Court were accepted by an overwhelming majority or unanimously by the judges of the Grand Chamber. However, the judges were divided (11 votes to 6) on a fundamental issue with far-reaching implications, that is, the question of whether the events occurring during the active phase of hostilities had or not fallen within the jurisdiction of the Russian Federation. The majority answered the question in the negative. Their main, in my view, not really convincing, argument was a “context of chaos” during the military confrontation. In armed conflicts there will usually be an element of chaos which cannot possibly be an argument for States to escape their responsibilities. A minority of judges answered the question in the affirmative. In their partly dissenting opinions some judges state their view vigorously. Judge Lemmens writes:

“I conclude that the alleged victims of the military operations carried out by the Russian armed forces during the active phase of hostilities fell within the jurisdiction of the Russian Federation. I regret that the majority have taken a step back and restricted the scope of the Convention in situations where human rights are at great risk.”(para. 3)

And Judge Pinto de Albuquerque states:

“…the Court will face a gargantuan task to restore the damage to its credibility caused by this judgment.”(para. 30)

I personally agree with the minority of judges. Unfortunately, the Court’s case law concerning the application of the European Convention on Human Rights in armed conflicts is hesitant and inconsistent. This is deplorable, not least because, unfortunately, in the area covered today by the Council of Europe, now a pan-European organization, and by the European Convention on Human Rights, armed conflicts are more likely and indeed more frequent than 30 or 40 years ago when the Council of Europe was a West European organization.

Will Russia comply with the judgment?

Grand Chamber judgments are final and the Russian Federation is under an obligation to comply with the judgment which will be transmitted to the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe for supervision of its execution.

Will Russia comply? Russia has become the main “customer” of the European Court of Human Rights. At the end of 2020, 62.000 applications were pending before the Court, 13.650 concerning Russia, nearly all of them individual applications, but also some State applications, five lodged by Ukraine, two of which are pending before the Grand Chamber (concerning Crimea and Eastern Ukraine), three before a Chamber. Russian authorities frequently criticize the Court as being “politicized”, “biased” and “anti-Russian”. Russia’s record of execution of judgments of the Court is far from perfect. A law of December 2015 gives the Russian Constitutional Court the power to decide on the “possibility” of executing judgments of the Strasbourg Court, thus defying its authority. This being said, it must be recognized that there are some positive “Strasbourg effects” for the Russian population, in individual cases and also, thanks to reforms as a result of case law from the European Court, some of which address systemic issues.

Suggested citation: Dr Peter Leuprecht, “Judgment of the European Court of Human Rights In the case Georgia vs. Russia” (2021), 5 PKI Global Justice Journal 6.

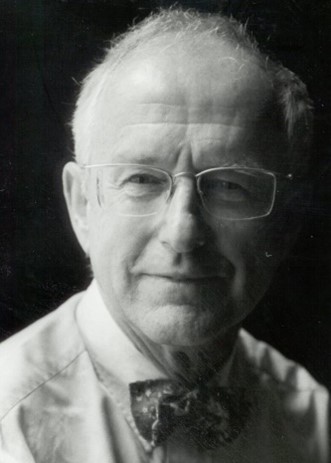

About the author

Peter Leuprecht. Doctor of law, University of Innsbruck (Austria). 1958-1961 Assistant lecturer at the Law Faculty of the University of Innsbruck and work at the Bar. 1961-1997 official in the Secretariat General of the Council of Europe (Strasbourg, France); 1976-1980 Secretary of the Committee of Ministers; 1980-1993 Director of Human Rights; elected Deputy Secretary-General in 1993; leaves his post before the end of his term because of disagreement with dilution of Council of Europe standards.

Peter Leuprecht. Doctor of law, University of Innsbruck (Austria). 1958-1961 Assistant lecturer at the Law Faculty of the University of Innsbruck and work at the Bar. 1961-1997 official in the Secretariat General of the Council of Europe (Strasbourg, France); 1976-1980 Secretary of the Committee of Ministers; 1980-1993 Director of Human Rights; elected Deputy Secretary-General in 1993; leaves his post before the end of his term because of disagreement with dilution of Council of Europe standards.

Has taught at the Universities of Strasbourg and Nancy (France) and at the European Academy of Law in Florence (Italy). Author of numerous publications in the field of international law and human rights, including the book “Reason, Justice and Dignity. A Journey to Some Unexplored Scources of Human Rights”, Martinus Nijhoff, Leiden-Boston, 2012. 1997-1999 Visiting Professor at the Faculty of Law of McGill University and at the Département des sciences juridiques de l’Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM) and advisor to the Canadian Department of Justice. From 1999 to 2003 Dean of the Faculty of Law of McGill University. From 2004 to 2008 Director of the Montreal Institute of International Studies and Professor of public international law at the Département des sciences juridiques de l’UQAM.

Member of a committee of four “Sages” which prepared a human rights Agenda for the European Union.

2000-2005 Special Representative of the Secretary-General of the UN for human rights in Cambodia.

Image: LukeOnThe Road/Shutterstock.com