May 25, 2021

Revisiting Gregory Gordon’s Groundbreaking Work “Atrocity Speech Law” as It Is Transformed from Book into Website

By: Giovanni Chiarini

I. Introduction

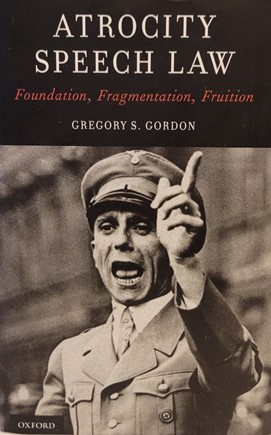

Since its initial publication in 2017, Chinese University of Hong Kong Law Professor Gregory Gordon’s paradigm-shifting work, “Atrocity Speech Law: Foundation, Fragmentation, Fruition” (Oxford University Press) has helped change the very vocabulary we use to describe the rules and jurisprudence governing the relationship between hate speech and core international crimes, which is now commonly referred to by the book’s title. Thanks to this seminal tome, we no longer have to think of delicts such as “incitement”, “persecution”, “instigation”, and “ordering” as disparate speech offences whose elements should not be considered with regard to one another; rather, under Gordon’s brilliant umbrella term and his suggested corrections for each offence, we can regard them in a unified, systematic way that will lead to more coordinated and coherent charging decisions, greater protection for legitimate free speech, and clearer jurisprudence (as will be explained below). After the book’s publication, the author was approached by the Yale University Genocide Studies Program (Yale GSP) with a proposal to convert it into a website that would make it even more accessible to experts and the lay public and update it to deal with recent hate speech issues.

Since its initial publication in 2017, Chinese University of Hong Kong Law Professor Gregory Gordon’s paradigm-shifting work, “Atrocity Speech Law: Foundation, Fragmentation, Fruition” (Oxford University Press) has helped change the very vocabulary we use to describe the rules and jurisprudence governing the relationship between hate speech and core international crimes, which is now commonly referred to by the book’s title. Thanks to this seminal tome, we no longer have to think of delicts such as “incitement”, “persecution”, “instigation”, and “ordering” as disparate speech offences whose elements should not be considered with regard to one another; rather, under Gordon’s brilliant umbrella term and his suggested corrections for each offence, we can regard them in a unified, systematic way that will lead to more coordinated and coherent charging decisions, greater protection for legitimate free speech, and clearer jurisprudence (as will be explained below). After the book’s publication, the author was approached by the Yale University Genocide Studies Program (Yale GSP) with a proposal to convert it into a website that would make it even more accessible to experts and the lay public and update it to deal with recent hate speech issues.

Professor Gordon and the Yale GSP, along with PROOF: Media for Social Justice, a Non-Governmental Organization that creates online exhibitions to engage the broader public in conversations about human rights and justice, were recently awarded a significant Project Impact Enhancement Grant from Gordon’s home institution to create the website. Apart from laying out Professor Gordon’s main points through a user-friendly architecture and design, the website will employ illustrative movie clips, moving first-hand testimonies and powerful photo narratives to put the book into greater perspective. For example, hate speech against Myanmar’s Rohingya Muslims will be featured and the project team expects to use videos of extremist Buddhist monk Ashin Wirathu’s incendiary rhetoric against them as well as interviews with targeted Rohingya. Moreover, images, narratives and clips will be included in reference to hate speech persecution campaigns in Rwanda and the former Yugoslavia, as well as earlier historical ones, such as the Holocaust and the Armenian Genocide. The work is expected to be completed later this year.

II. Review of “Atrocity Speech Law: Foundation, Fragmentation, Fruition” (Oxford University Press 2017)

In light of this important new project, it makes sense to revisit the powerful achievement of Gordon’s magnum opus. As observed in the Foreword by the ICL titan Benjamin Ferencz, this book “is an important contribution that will serve as a foundation stone for the future prevention of crimes against humanity”. Like its subtitle, the book is divided in three parts: (1) Foundation; (2) Fragmentation; (3) Fruition. Each of those reflects a stage in the life of this body of law.

A. Part 1: Foundation

Even if Part I collaterally analyzes the main convention and part of the essential jurisprudence of the European Court of Human Rights, it is principally dedicated to history. The author goes in-depth into the terrible scars of the past, from the Pre-World War II era to the most recent cases of Kenya, Côte d’Ivoire and Myanmar. In these historical sketches, Gordon provides the background leading to the atrocities and related hate speech campaigns, the major actors responsible for fomenting the speech and violence, the media used for disseminating the toxic rhetoric, examples of the rhetoric, and discussions of the relationship between the speech and the mass violence. In this in-depth and invaluable reconstruction, he features the preponderant archetypal propaganda cases: the Armenian Genocide (recently officially recognized by US President Joe Biden), spurred by the Ottoman vilification campaign; the Holocaust, fueled by the key Nazi anti-Semitic propagandists; the Post-Cold War Balkan atrocities and the poisonous spark of Bosnian Serb rhetoric; as well as the Rwandan Genocide, and the sine qua non of extremist Hutu hate speech.

The core of Part I is to be found, in my opinion, in the birth of what Professor Gordon brilliantly designates as “atrocity speech law” (as suggested above, a body of law that hitherto lacked a name). As Gordon demonstrates, its foundational jurisprudence can be divided into two parts: first, it is to be found in the judgments of the Nuremberg Trials (p. 103 of Atrocity Speech Law)); second, it is developed in the cases decided by the ad hoc Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and Rwanda (ICTR) (p. 135), especially in respect of the fleshing out of the offense elements. Thus, these Tribunals created a “foundational body of jurisprudence for the speech-related criminal modalities” (p. 181). But unfortunately, these principles, which were initially developed via Crimes against Humanity charges at Nuremberg (against Nazi propagandists Julius Streicher, Hans Fritzsche and Otto Dietrich) and then pursuant to rules laid down in the Genocide Convention and the ad hoc tribunal statutes, were not meant to have a bright future.

B. Part 2: Fragmentation

Part II examines the problems regarding the speech offences previously considered – direct and public incitement to commit genocide (speech calling for genocide but which does not result in such), persecution as a crime against humanity (hate speech issued as part of a widespread or systematic attack against a civilian population), instigation (calling for the commission of atrocities when they are subsequently committed), and ordering (a command to commit atrocities in the context of a superior-subordinate relationship). As insightfully revealed by Professor Gordon, “the tribunals, as well as certain domestic jurisdictions, where relevant, refused to exercise any kind of stewardship role toward the emerging framework” (p. 182). The effects of this judicial approach, which led to confusion in the law (such as mixing up the elements of incitement with the elements of instigation and not using the articulated tests for the offences consistently across judicial decisions) Gordon defines as “pernicious”, and they are critically analyzed in Part II of the book.

Professor Gordon delves deeply into the jurisprudence developed by the ICTR/ICTY and inherited by the ICC, thus offering an important and clear account and analysis of many complicated issues, such as striking the delicate balance between charging illicit hate speech and protecting legitimate free speech in relation to an attack on civilians (pp. 336-341).

Noteworthy is the chapter dedicated to the liability gap in reference to hate speech and war crimes: “if the hate speech-core crime relationship is plagued by international incoherence with respect to incitement to genocide and instigation and institutional incompatibility as concerns persecution, the problem in reference to war crimes is quite different. In effect, the issue is relative absence of law” (p. 253). Since international humanitarian law contains no hate speech provisions, Gordon explores the “deadly implications” of that normative vacuum and details the relevant legal instruments that evidence it. This short chapter is dense and infused with history. It contains speeches of military personnel in the atrocity context as well as speeches of civilians inciting military personnel and, obviously, the issue of military speeches within the modern history of war crimes (such as US General Jacob Smith in 1901 urging troops to turn a civilian area into a “howling wilderness” in the Philippine-American War (Atrocity Speech Law, pp. 254-55) to officers in Thomas Lubanga’s Union of Congolese Patriots describing women as objects of sexual desire to their soldiers such that mass rape of females in the vicinity ensued (Atrocity Speech Law, pp. 260-61).

C. Part 3: Fruition

Needless to say, Part III is the core of this impressive tome. And as a “diamond”, with many brilliant facets, it must be looked at closely, attentively, carefully. This part makes a bold and innovative contribution to the literature: a Unified Liability Theory for Atrocity Speech Law (p. 367). This would fill in gaps in the existing law, such as having incitement apply to all the core crimes, not just genocide (for example, as we have just seen, could be done with war crimes). And it would create a new offense, speech abetting, which would criminalize speech uttered contemporaneously with atrocity (what Gordon calls “egging on” speech – currently only crimes against humanity (persecution) covers such contemporaneous hate speech but speech abetting would apply to all the core crimes).

Readers should be aware that, like any new and visionary scientific discovery, this theory will not be quickly and superficially digested, especially given that it is part of a groundbreaking legal framework still in its early phases of development. But Gordon aids the reader with the section of the book called “Theoretical and Practical Issues Raised by the Unified Liability Theory.” This passage is invaluable as it clarifies such potentially thorny issues, inter alia, as the doctrinal and policy relationship between speech abetting and persecution, the possibility of double inchoate crimes and the logistics of multiple and/or alternative charging in relation to the various speech delicts. And thus, as this passage suggests, although it will require thoughtful and dedicated implementation with great attention to detail to put the Unified Liability Theory into practice, given how it will improve and harmonize the law, I believe it will be well worth the investment. This is especially true given that the theory, and Gordon’s book in general, recognizes the value of free speech and engages in the difficult balancing act of protecting it versus hate speech (see, for example, pp. 336-41, suggesting limits on persecution as a crime against humanity in light of liberty of expression concerns).

For its operationalization, Gordon proposes an eight-article Convention on the Classification and Criminalization of Atrocity Speech Offenses, and/or an amendment of the Rome Statute adding Article 25bis, entitled “Liability Related to Speech”. The Convention could be useful for domestic jurisdictions and newly created ad hoc tribunals. It would include a preamble specifying the object and purpose of the treaty as well as eight articles defining the foundational terminology, laying out the elements of the speech offences, and establishing jurisdiction, and mandating domestic legislation. Modification of the ICC’s Statute would entail taking out of existing Article 25 the modalities of ordering, soliciting, inducing and inciting and moving them to the new Article 25bis, which would expand the scope of incitement to cover the other core crimes, expand ordering to make it an inchoate offence (it currently only applies to orders actually carried out, despite the high likelihood of commission in the context of a superior-subordinate relationship) and add the offence of speech abetting.

The book’s conclusion draws attention to the fact that properly identifying atrocity speech law, and fixing it, does not necessarily provide a “silver bullet” solution. In particular, Gordon emphasizes that “in regulating human decency, the law’s writ is circumscribed. It cannot legislate civic grace or decorum. It cannot enjoin hate. But it still has a role to play in regulating verbal conduct that helps foment the most unspeakable crimes.” (p. 421). Aware that the main way to prevent this type of criminality is primarily via civic education, we must not, at the same time, forget that the law should not abdicate its own important role.

III. Conclusion

And this is where the website will add great value. One weakness of the book is that it does not comprehensively cover the important issue of social media and atrocity speech. Certainly, a reasonable explanation for this is that the book deals with jurisprudence developed primarily in relation to the Holocaust, the Rwandan Genocide and 1990s atrocities in the former Yugoslavia. Propaganda campaigns in relation to those older cases were not conducted via social media. The website will provide a valuable update by including a “Beyond the Existing Jurisprudence” section that will explore important issues raised by atrocity speech and social media, such as the need for a reasonable formulation of “community standards” and human-curated algorithms to help quickly take down weaponized rhetoric once it is posted. Moreover, this part of the website will explain, in more concrete terms, how educational institutions and civil society might team up to counter atrocity speech (via, for example, reporting such speech to NGOs and teaching individuals how to effectively counter it online or via text message, as has been done innovatively through the Sentinel Project’s Una Hakika program in Kenya). More directly, in schools themselves, such as those in the Palestinian Authority, where the EU Parliament has recently raised concerns over anti-Semitic incitement to violence against Israelis in textbooks, removing the incendiary material could make a very important difference.

And, in a larger sense, that is what Professor Gordon’s book is all about – finding creative and integrative solutions for defeating atrocity speech. And, in reference to the existing jurisprudence, that is the approach that Gordon is urging the legal community to take. Thus, the book issues a clarion call to the ICL community and to the State Parties of the Rome Statue to put this area of the law in order. That call could be nicely amplified by the website conversion project. And, given the well-established link between hate speech and atrocity, we, international criminal lawyers, cannot afford to stand idly by and ignore it. I am convinced that the echo of Gordon’s cri de coeur will resound and be heard where it needs to be heard. Or at least, I hope so. Certainly, the launch of new online platform later this year gives me much more optimism.

Suggested citation: Giovanni Chiarini, “Revisiting Gregory Gordon’s Groundbreaking Work “Atrocity Speech Law” as It Is Transformed from Book into Website” (2021), 5 PKI Global Justice Journal 22.

About the author

Giovanni Chiarini is an Attorney at Law (Bar Council of Piacenza, Italy), qualified as Assistant to Counsel at the International Criminal Court (The Hague). He interned at the Supreme Court Chamber of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), with the United Nations Assistance to the Khmer Rouge Trials (UNAKRT). PhD candidate in International and Comparative Criminal Procedure at Insubria University (Como and Varese, Italy) and Visiting Fellow at the Laboratoire de Droit International et Européen, Université Côte d'Azur (Nice, France). His research is mainly focused on the juridical nature of International Criminal Procedure, between Common Law and Civil Law.

Giovanni Chiarini is an Attorney at Law (Bar Council of Piacenza, Italy), qualified as Assistant to Counsel at the International Criminal Court (The Hague). He interned at the Supreme Court Chamber of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), with the United Nations Assistance to the Khmer Rouge Trials (UNAKRT). PhD candidate in International and Comparative Criminal Procedure at Insubria University (Como and Varese, Italy) and Visiting Fellow at the Laboratoire de Droit International et Européen, Université Côte d'Azur (Nice, France). His research is mainly focused on the juridical nature of International Criminal Procedure, between Common Law and Civil Law.

Image: Cover of “Atrocity Speech Law: Foundation, Fragmentation, Fruition” by Gregory S. Gordon, © Oxford University Press 2017, used with permission of Oxford University Press and under license through PLSclear.