( Title Image: " Den Haag - Vredespaleis” | Fred Romero | cc-by-2.0 )

Table of Contents

- Alex Neve and Sharry Aiken, Introduction: Human Rights and the International Court of Justice: Challenges and Opportunities

- Bill Schabas, Towards a Global Human Rights Court

- Kathleen Gant, An Interview with Payam Akhavan

- Mark Kersten, Courts in Conversation: The International Criminal Court, the International Court of Justice and their mutual and respective roles in Addressing International Crimes

- Sara Seck and Penelope Simons, The ICJ Advisory Opinion on Climate Change: Potential Implications for the Business and Human Rights Normative Framework

- Christopher Campbell-Duruflé, An Epitome of Modern Environmentalism: Canada’s Contribution to the ICJ Advisory Opinion on Climate Change

- Heidi Matthews, ‘Preventing births’ as a gender-neutral harm: Making sense of reproductive violence in South Africa’s genocide case against Israel

- Faisal A. Bhabha, Anti-discrimination at the ICJ: Ukraine, Palestine and the Freedom to Advocate for Human Rights in Canada

- Michael Lynk, Racial Segregation and Apartheid: The International Court of Justice’s Advisory Opinion on the Discriminatory Features of Israel’s Occupation of Palestine

- Ardi Imseis, Paradigm Shifts and the Palestine Moment: On the International Court of Justice and the Quest to Save International Law

Introduction: Human Rights and the International Court of Justice: Challenges and Opportunities

by Alex Neve and Sharry Aiken

The level of awareness and interest in both the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court has grown noticeably in recent years; not simply within legal and international affairs circles, but among the general public. That tracks with a caseload at both courts that reflects a range of countries and pressing issues that are of considerable interest and concern to people across the world, including the climate crisis, and grave human rights violations in Gaza, Myanmar, Afghanistan, the Ukraine and Syria. As such, judicial bodies that have often been overlooked by the public have gained a strong sense of relevance.

That is particularly the case with the International Court of Justice. In late 2024, Alex was invited to give a talk to a roundtable of about thirty business professionals in Ottawa, very few of whom had any particular knowledge of international legal standards or institutions. He had been asked to talk about the potential role of international law in resolving the crisis in Gaza. He began asking the group how many would have raised their hand at a similar session one year earlier, in 2023, if asked if they had ever heard of the International Court of Justice. Only two people raised their hands and both indicated that while they were aware of the court at that time, they had no understanding of its mandate or how it worked.

Alex then asked the group how many had now heard of the International Court of Justice, and this time all but two of the group raised their hand. When further asked what they knew about the ICJ, most responses described some variation of it being a court where governments were held accountable for violating international law. As the conversation proceeded, it was also clear that many of the roundtable participants were uncertain of the differences between the ICJ and the ICC, and some had confused the former for the latter.

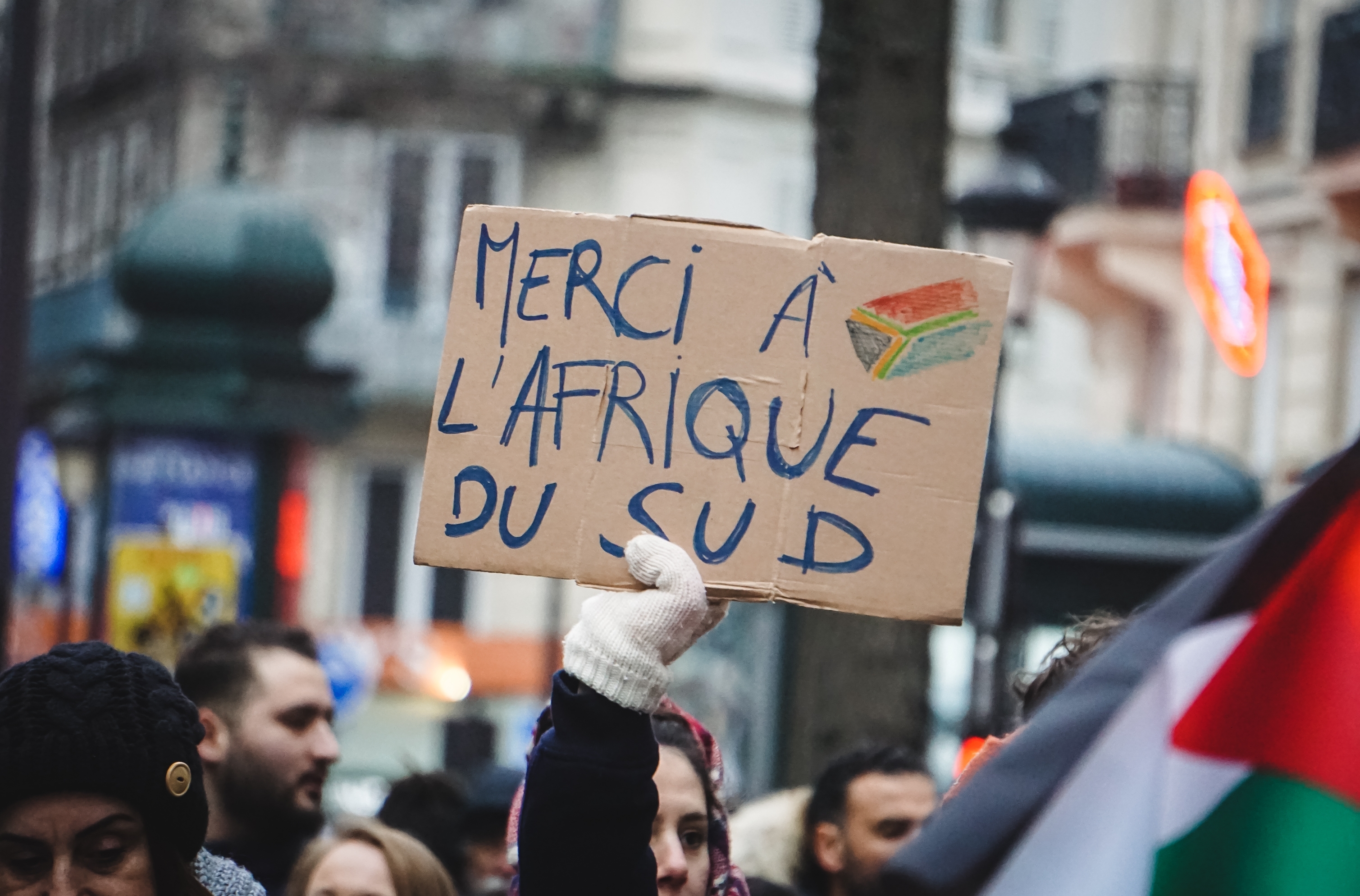

Much of the increased attention on the work of the ICJ does of course arise because of considerable media and social media coverage and discussion of the case that South Africa has brought against Israel under the Genocide Convention regarding the situation in Gaza. But as the roundtable discussion continued, there was considerable interest in other cases before the court. One participant eventually asked, is this the world’s human rights court?

That is the question we have asked the contributors to this special issue to explore. Is the International Court of Justice becoming, in some fashion, a human rights court? If so, what does that represent? What are the strengths and weaknesses of viewing the ICJ as a human rights court? What are the challenges it faces in playing such a role? Are there opportunities to take that further? What of the relationship between the ICJ and the ICC?

The time for examining these questions is both opportune and pressing. There is much lament and debate about the ways that the international rules-based order is increasingly strained and refuted, including by many of the world’s most powerful governments. The disdain demonstrated, for instance, by governments in Washington, Moscow and Beijing for international law and for institutions such as the ICJ is abundantly evident. At a time when international law faces considerable challenge, the fact that there is growing interest in and awareness of the ICJ and its potential to assist in enforcing international human rights standards, is notable and, perhaps, offers some reassurance or at least encouragement.

The contributors to this special issue have considerable expertise and experience following and analyzing key human rights related cases that have come before the ICJ in recent years. Several of the authors have been part of legal teams that have argued or intervened in those cases, and several are also experts in the work of the International Criminal Court.

Professor William Schabas’ article, Towards a Global Human Rights Court, asserts that “suddenly, and unexpectedly, the International Court of Justice has emerged as a global human rights court.” He notes that in many respects this fills a gap left by the unmet ambition, dating from the earliest days of the United Nations, to establish a dedicated international human rights court, a proposal that continues to have currency but appears unlikely to be realized. Schabas surveys a number of ICJ cases touching on human rights and concludes that we should find reassurance, in these troubled times from the fact that the UN’s principal judicial organ is “increasingly focused on human rights,” and is doing so with the apparent “confidence of a large number of States from different parts of the world.”

We have included an abridged and edited transcript of an interview with Professor Payam Akhavan. He begins by disagreeing with the proposition that the ICJ operates as a human rights court, particularly because victims of human rights violations themselves have no standing and are unable to initiate proceedings at the court. He notes nonetheless that there has been a marked increase in human rights-related cases at the ICJ in recent years, beginning with the case brought by the Gambia against Myanmar under the Genocide Convention in 2019. Like Schabas, Akhavan also posits that this is in part an outcome of the fact that the world lacks a true human rights court. Despite the challenges faced by the ICJ he is optimistic that states will increasingly respect its role, given that the major threats to peace, security and, with the climate crisis, even planetary survival that we face, are all global in their origins and their impact, and thus require global adjudication and enforcement.

Professor Mark Kersten’s contribution, Courts in Conversation: The International Criminal Court, the International Court of Justice and their Mutual and Respective Roles in Addressing International Crimes, considers the relationship between the ICJ and the ICC, given that both courts have increasingly found themselves seized of the same situations of mass atrocity crimes, including in Gaza, Myanmar, Ukraine and Afghanistan. He examines their different but also overlapping roles. He considers the work of the two courts by looking at their respective abilities to galvanize state engagement and support, how readily they are able to withstand political interference and pressure, and the extent to which they are able to enforce their decisions. Ultimately, he encourages more attention to the ways in which the two courts might enter into dialogue with each other in ways that “foster greater accountability for international crimes.”

The next two articles consider the role of the ICJ as a human rights court in relation to the global climate crisis, with a consideration of the impact of the Advisory Opinion on climate change that has been sought from the court by the UN General Assembly. At the time this special issue was being finalized the hearings in relation to that Advisory Opinion had been concluded, but the opinion had not yet been rendered.

In their contribution, The ICJ Advisory Opinion on Climate Change: Potential Implications for the Business and Human Rights Normative Framework, Professors Sara Seck and Penelope Simons note that the Advisory Opinion could be consequential for the international business and human rights framework. They consider the potential for the court to elaborate the extent to which the obligation of states to protect human rights includes a duty to exercise due diligence with respect to private actors, such as businesses, to ensure that they do not violate the rights of individuals and communities. They will be looking to see what the court has to say regarding the extent to which that duty “includes the obligation to take regulatory, administrative and other action and, where human rights violations occur, to investigate and provide effective remedies.” They note as well that the court’s conclusions as to the normative status of the right to a clean, healthy and sustainable environment will have broad implications for business and human rights.

Professor Christopher Campbell-Duruflé’s article, An Epitome of Modern Environmentalism: Canada’s Contribution to the ICJ Advisory Opinion on Climate Change, critically assesses the written and oral submissions made by the Canadian government as part of the Advisory Opinion proceedings. He summarizes three main themes that emerge from those submissions: that there is not yet a customary international norm related to the obligation to avoid causing climate harm, the specific norms in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Paris Agreement have displaced other more general international norms, and that there are significant limitations in approaching climate change through a human rights framework. Campbell-Duruflé concludes that Canada’s position is disappointing, though not surprising. He suggests that this provides “Canadians an occasion to reflect on whether they prefer a rules-based global response to the climate emergency or one that privileges unilateral action.”

In her contribution, ‘Preventing births’ as a gender-neutral harm: Making sense of reproductive violence in South Africa’s genocide case against Israel, Professor Heidi Matthews engages critically with the nature of the arguments advanced by South Africa at the ICJ regarding the extent to which measures taken by Israel, intended to prevent Palestinian births in Gaza, fall within the Genocide Convention. She asserts that this provision of the Convention should not be limited, as is customary, to conflict-related sexual and gender-based violence, primarily assessed in relation to the rights of women and girls. She advances an alternative analytical framework which focuses on reproductive violence committed against all genders. Matthews draws upon findings of the UN Human Rights Council’s International Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and Israel, regarding the “potential harm to [Palestinian] men and boys’ reproductive capacity and their willingness to procreate in the future” and argues that the ICJ has an important opportunity to recognize that “Palestinians of all genders have been subjected to widespread and systematic biological violence aimed at impairing the capacity of the Palestinian group to regenerate itself as such.”

Professor Faisal Bhabha’s article, Anti-discrimination at the ICJ: Ukraine, Palestine and the Freedom to Advocate for Human Rights in Canada, concentrates on recent ICJ cases with respect to Ukraine and Israel-Palestine, that have been brought under or have significantly drawn on the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD). Bhabha highlights several key principles from those two cases, finding a broad conception but narrow application of anti-discrimination law with respect to the Russian occupation of Crimea, and an all-encompassing conclusion that the overall situation in Occupied Palestinian Territory constitutes racial discrimination. He then considers a range of Canadian court cases and government policies dealing with anti-Palestinian racism, antisemitism, and Palestinian solidarity protests. He looks closely at efforts to implement the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s controversial definition of antisemitism in Canada. He concludes that the ICJ’s reasoning with respect to racial discrimination should provide some legal protection to activists who face penalties for engaging in the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement.

The final two contributions engage directly with the ICJ’s recent rulings with respect to Israel and Palestine.

Professor Michael Lynk’s article, Racial Segregation and Apartheid: The International Court of Justice’s Advisory Opinion on the Discriminatory Features of Israel’s Occupation of Palestine, considers the approach the ICJ takes to assessing the discriminatory nature of Israel’s occupation. He notes that in its Advisory Opinion on Israel’s occupation of Palestinian Territory, the Court focuses on three dimensions of the occupation, namely the residence permit policy in occupied East Jerusalem, restrictions on movement that Israel has imposed on Palestinians living in the occupied West Bank, and Israel’s practice of demolishing Palestinian homes and properties in the West Bank and East Jerusalem. He stresses that in finding that Israel has violated article 3 of CERD, the ICJ has effectively concluded that Israel is responsible for both racial segregation and apartheid, the first time an international court has reached that conclusion. Lynk highlights that this is a significant addition to the “growing international consensus on the prevalence of apartheid as an integral feature of Israel’s occupation of Palestine.”

This special issue concludes with Professor Ardi Imseis’ powerful article, Paradigm Shifts and the Palestine Moment: On the International Court of Justice and the Quest to Save International Law. Imseis underscores that despite 80 years of developing international legal norms and institutions, the current genocide in Gaza has become the “inflection point for world order”. He notes that “under the weight of Western hegemonic support of Israel’s onslaught against the Palestinian people,” middle and smaller powers, mostly but not exclusively from the Global South, are increasingly turning to the ICJ for redress. He provides an overview of the four current ICJ cases dealing directly with the situation in Gaza and also the broader question of Israel’s occupation of Palestinian Territory. He emphasizes the particular importance of the ICJ’s Advisory Opinion regarding the legal status and implications of Israel’s occupation, which he describes as a “paradigm shift” when it comes to the law and politics of the “Palestine question.” It has led to a “structural change” which we must now “collectively activate.”

These nine thoughtful and, at times, provocative and challenging articles make it clear that the human rights caseload of the International Court of Justice has increased markedly in recent years, across a range of countries and a variety of human rights concerns. That is in part a reflection of legal ingenuity but, more pointedly, it highlights the mounting, widely felt need to shore up the international legal order in the face of contempt and disregard for crucial international norms. While the advent of a true world human rights court is an unlikely prospect in today’s global geopolitical context, there is every likelihood of more human rights cases being heard in The Hague. As public awareness of the ICJ’s role as a guardian of human rights grows, the challenge ahead lies in working to ensure that governments adhere to its rulings.

________________________________________

Citation: Alex Neve and Sharry Aiken, Human Rights and the International Court of Justice — Challenges and Opportunities: a special issue of the PKI Global Justice Journal (2025) 9 PKI Global Justice Journal 5.

Stephanie Kenner | shutterstock.com

Towards a Global Human Rights Court

by Bill Schabas

The proposal to establish an international human rights court is credited to the Australian delegation, headed by Herbert Evatt, at the 1946 Paris Peace Conference. At the first session of the United Nations Commission on Human Rights, in February 1947, Australia tabled a formal proposal on the subject. Belgium suggested to the Commission that such an institution might take the form of a special chamber of the International Court of Justice.

From time to time, the idea of a world court of human rights has resurfaced, most recently in a campaign led by Manfred Nowak and Martin Scheinin. The proposal never seems to get much traction. The difficulty in advancing this on the international agenda has always seemed a bit of a paradox given the huge success of regional human rights courts as well as the enthusiastic support for the creation of other specialised global courts like the International Criminal Court.

Rather suddenly, and unexpectedly, the International Court of Justice has emerged as a global human rights court, although perhaps not the one Australia had imagined. No political initiative or legislative change has been involved, nor is any policy decision of the Court itself responsible for this development. Unlike the regional human rights courts, there is no individual petition mechanism although the door has always been open to States challenging the treatment of their own nationals. The International Court of Justice operates within the framework of its Statute, adopted in 1946. Its decisions consist of judgments in inter-State cases and advisory opinions. But then regional human rights courts (and treaty bodies) also tackle inter-State litigation and issue advisory opinions or something analogous.

Commentators have often been rather dismissive of the role of human rights at the International Court of Justice. A book chapter by Carlos Esposito in the Cambridge Companion to the ICJ, published in 2023, speaks of “the restricted and scarce role” and the “disengagement” of the Court in the field of human rights. But I think this publication is already woefully out of date. Esposito explains that the reason for the relative lack of engagement of the Court in the field of human rights is because it is an institution where only States can bring cases. It is true that until recently States have been extremely reluctant to litigate human rights issues. The inter-State dispute settlement provisions of the main human rights treaties were rarely invoked. For example, article 41 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, in force for half a century, has never been applied.

This is no longer the case. Indeed, it is States that have chosen to take human rights issues to the International Court of Justice, often acting in the interests of the enforcement of international law rather than because they have some identifiable injury. They are joined, massively in some cases, by other States who intervene pursuant to articles 62 and 63 of the Court’s Statute. And it is States that have voted to request advisory opinions from the Court. The issues in both the contentious cases and the advisory opinions are matters that previously were reserved for political bodies like the General Assembly, the Human Rights Council, and the Governing Body of the International Labour Organization.

That human rights law falls within the subject-matter jurisdiction of the Court is not controversial. Sporadically, over the nearly 80 years since it began its activities, the Court has addressed issues that bear on fundamental rights and freedoms. Even its predecessor, the Permanent Court of International Justice, which operated from 1920 to 1945, issued judgments on such issues as education rights of minorities and the principle of legality. The first contentious case before the International Court of Justice addressed “elementary considerations of humanity, even more exacting in peace than in war”. A series of advisory opinions, punctuated by an unfortunate contentious case, resulted in firm condemnation of the apartheid regime imposed upon Namibia by South Africa. There were several genocide cases, none of them crowned with great success, and some rulings against the United States concerning the imposition of the death penalty. But human rights was never the bread and butter of the International Court of Justice. That is, until recently.

As of 1 January 2025, some 22 cases were pending before the Court and two were under deliberation. About half of them bear on human rights matters. The list includes three requests for advisory opinions, all of them dealing, at least in part, with human rights. Four contentious cases concern application of the Genocide Convention, two the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, and one the Convention Against Torture. Moreover, there is a very public initiative from some States, including Canada, to bring a case against Afghanistan based on the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women.

This is a situation without precedent in the history of the Court. Indeed, the Court went for several years with an extremely sparse case load after it stumbled, in 1966, in a notorious judgment that favoured South Africa. Its image improved somewhat in the mid-1980s when it ruled against the United States for attempting to overthrow the government of Nicaragua. Freedom of movement from the perspective of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights was the theme in a diplomatic protection case filed by Guinea against the Democratic Republic of the Congo more than fifteen years ago. Judge Cançado Trindade, a great enthusiast for human rights, described the Court’s 2010 judgment in that case as a “turning point”.

But the real turning point came much later, in February 2019, with issuance of its advisory opinion on the Chagos Islands. The Court condemned the United Kingdom for snatching the territory from Mauritius at the time of decolonization in order to hand it over to the United States for an important military base. The indigenous population was ethnically cleansed in order to facilitate the repurposing of the archipelago. The General Assembly resolution requesting the advisory opinion was proposed by 54 African States who sought, according to their spokesman, “to complete the decolonization of Africa”. London fought bitterly but unsuccessfully in the General Assembly to prevent the request. When the case was heard, it lacked a judge of British nationality on the bench after being beaten in the elections that year by the Indian candidate.

The Chagos advisory opinion seemed to send a signal of an increasingly progressive and dynamic court. Late in 2019, Gambia filed an application against Myanmar based upon a provision in the Genocide Convention. A unanimous provisional measures order directed against Myanmar followed in January 2020. Gambia is acting erga omnes and it is no secret that it is being backed, politically and financially, by the 57-member Organization of the Islamic Conference. In other words, a large number of States are behind the case. Eleven States, most of them European, have formally intervened in the case to support Gambia.

Since then, three more cases based on the Genocide Convention have been launched. The Ukraine v. Russia case sparked thirty-three interventions. In South Africa v. Israel there are now thirteen interventions, and more are to be expected. There are none yet in Nicaragua v. Germany but it is still early days. Until these genocide cases were filed, starting with Gambia v. Myanmar, in the entire history of the Court there had been only a small handful of interventions in contentious cases, and only one that was successful. They were all by States that were directly concerned in the outcome, and not, as is now the case, States acting in the common interest, erga omnes or erga omnes partes. The modern tsunami of interventions, like several of the cases themselves, are all from States that are not ‘injured’.

The extraordinary interest in these cases seems to signal a desire that the Court use the Genocide Convention in a more effective way than it has done in the past. Although eighteen cases premised on the Genocide Convention have been filed in the Court over the past half-century, it has yet to hold a State liable for the commission of genocide. The joint intervention in the Gambia v. Myanmar case by Canada and five European States argues for a more liberal interpretation of the Genocide Convention than the Court has adopted in its previous judgments. These States stress the importance of factors like internal displacement and the victimisation of children in assessing the presence of genocidal intent. They invoke a dissenting opinion by Judge Cançado Trindade calling for a more flexible approach to proof of genocidal intent. These arguments are most helpful and not only to Gambia. They also bolster South Africa’s case against Israel, although this was surely not what Canada and the others intended.

Human rights treaty bodies may be somewhat anxious about the consequences of this new direction for the International Court of Justice. Inevitably, the jurisdictions overlap, raising concerns about fragmentation. When the Court examined the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, in the Diallo case, it showed considerable respect for the expertise of the Human Rights Committee. But there was less deference for the treaty body when the Court interpreted provisions of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, in Qatar v. Emirates.

By resorting to the International Court of Justice, States demonstrate a confidence and a respect that goes well beyond their approach to human rights treaty bodies. For example, Canada has been somewhat dismissive of the authority of treaty bodies. In its fifth periodic report to the Human Rights Committee, Canada recalled ‘the non-binding nature of the Committee’s views’ and sought to justify its refusal to comply with interim measures ordered by the Committee. It returned to the point in its sixth periodic report, stating that “neither the Committee’s interim measures requests nor its Views are legally binding on States parties”. But when Canada’s legal advisor, Alan Kessel, addressed the International Court of Justice in October 2023 to request a provisional measures order against Syria, he recalled that these “have a binding effect and thus create international legal obligations for any party to whom the provisional measures are addressed”. Canada also signed a statement recalling that the Court’s provisional measures are “legally binding on the parties to the dispute”, and that Russia’s failure to comply with the 16 March 2022 Order in Ukraine v. Russia was ‘a further breach’ of international law. Predictably, when the Court granted South Africa’s request for an Order against Israel, in January 2024, Canada was more circumspect. It did not remind Israel that this was ‘binding’ although it politely recognized “the ICJ’s critical role in the peaceful settlement of disputes and its work in upholding the international rules-based order”.

The phenomenal turn towards the International Court of Justice, manifested in the requests for advisory opinions, the contentious cases filed by States acting erga omnes, and the massive number of interventions, points to a penchant for judicial settlement of disputes that concern human rights. Hitherto, such issues were addressed in political bodies like the Human Rights Council, the General Assembly and the Security Council. But these bodies are plagued with double standards. States speak with a forked tongue, denouncing the violations attributable to their enemies while ignoring those of their friends. It is harder to do this in a judicial forum, a lesson some of the intervening States in the Myanmar case have now learned.

The Court’s great authority has been enhanced by its ability to issue judgments, orders and opinions that are nearly unanimous. The curricula of its judges is more than impressive. Members include alumni of human rights treaty bodies, distinguished academics and experts from the International Law Commission. But there is a certain fragility to its current prestige. Great expectations accompany the current enthusiasm for the Court. States expect it to deliver progressive and creative interpretations of legal texts like the Genocide Convention that are in line with contemporary values.

The Advisory Opinion on the Occupied Palestinian Territory of 19 July 2024, declaring Israel’s occupation to be unlawful, calling for it to come to an end, and demanding that States contribute to this process, stands out as one of the Court’s greatest judicial pronouncements. But often overlooked is the order on provisional measures in Nicaragua v. Germany, issued a few months earlier, in which the Court went beyond the instructions to the parties themselves, acting ultra petita, in declaring it “particularly important to remind all States of their international obligations relating to the transfer of arms to parties to an armed conflict” so as to avoid the risk that such arms be used to violate the Genocide Convention, the Geneva Conventions and the Hague Conventions.

In its judgment on preliminary objections in Ukraine v. Russia, issued in early 2024, the Court recalled “its responsibilities in the maintenance of international peace and security as well as in the peaceful settlement of disputes under the Charter of the United Nations and the Statute of the Court”. That the principal judicial organ of the United Nations is increasingly focused on human rights, including the right to peace, and that it appears to enjoy the confidence of a large number of States from different parts of the world, is reassuring in these troubled times.

________________________________________

Citation: Bill Schabas, “Toward A Global Human Rights Court” in Human Rights and the International Court of Justice – Challenges and Opportunities: a special issue of the PKI Global Justice Journal (2025) 9 PKI Global Justice Journal 5.

About the Author:

William A. Schabas is professor of international law at Middlesex University in London, emeritus professor at Leiden University and the University of Galway, distinguished visiting faculty at the Paris School of International Affairs, Sciences Po, and an associate tenant at 9BR Barristers Chambers in London. The third edition of his book Genocide in International Law was published in March 2025. Professor Schabas is an Officer of the Order of Canada and a member of the Royal Irish Academy. In 2014 he served as chairman of the UN Commission of Inquiry into the Gaza conflict.

An Interview with Payam Akhavan

by Kathleen Gant

PKI Global Justice Journal Kathleen Gant interviewed Professor Akhavan, the inaugural holder of the Massey Chair in Human Rights at the University of Toronto about his views regarding human rights related cases that have been taken up at the International Court of Justice in recent years. There has been a growing number of such cases, including under the Genocide Convention, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, and the Convention Against Torture. PKI canvassed Professor Akhavan’s views on the significance of this growing human rights caseload, and whether we can or even should start to view the ICJ as a human rights court.

The interview took place on February 18, 2025 and is edited slightly for length and flow.

Kathleen Gant (KG): Professor Akhavan, thank you so much for taking the time to share your views with PKI Global Justice Journal. We appreciate your thoughts about the role the International Court of Justice plays in upholding international human rights obligations. We're particularly fortunate to have valuable insights from someone such as yourself, who has direct experience of being before the ICJ in high-profile human rights cases.

So let's begin with a fairly general question. Would you say it is a fair and accurate description of the International Court of Justice to say that it is a human rights court?

Payam Akhavan (PA): It is definitely not accurate. The ICJ is not a human rights court, it is a court that is predominantly mandated to resolve interstate disputes, and individuals have no standing to initiate proceedings before the court. Unlike the European Court of Human Rights, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the African Court of Human Rights. So the only possibility of initiating proceedings before the ICJ related to human rights is in the context of interstate proceedings.

And then there is also the advisory opinion function of the court, which is really not a contentious proceeding. It is at the request of the UN General Assembly, or other UN organs and agencies that such a request is made, and while opinions of the courts in advisory proceedings are not binding, they are authoritative statements of law and can have some influence.

But still even advisory proceedings have to be requested in the context of States making a decision within the context of UN organs or specialized agencies. So that's why the ICJ is not a human rights court.

KG: Following that question, there appears to be a growing number of cases brought by states at the ICJ under a number of key UN human rights treaties, including the Genocide Convention, the Convention against Torture, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, and likely in the near future, the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women. What do you think accounts for all that?

PA: It is quite a remarkable and unprecedented period of human rights-related litigation before the Court. In the 1960s, Ethiopia and Liberia brought a historic case against South Africa in relation to South West Africa, today known as Namibia. South Africa, contrary to the mandate system of the League of Nations, by which it inherited South West Africa as a trust territory until such time as it could achieve independence, decided instead to annex that territory. That case was remarkable in the sense that it was based on what we call actio popularis litigation, where the applicant States were themselves not directly injured, but they invoked international human rights law in a wider sense, as obligations erga omnes, or owed to the international community as a whole.

[The Court found that Ethiopia and Liberia lacked a sufficient legal interest to bring the claims because they were not directly affected. The case was seen as a setback for the enforcement of international human rights.] The [South West Africa cases] were for some time the end of actio popularis litigation; until more recently, which I will come to in a moment.

Now, throughout the history of the court there have been instances of human rights litigation where a state had a direct interest, even during the time of the League of Nations. When the ICJ was known as the PCIJ, the Permanent Court of International justice, there were several notable cases dealing with the rights of national minorities, pursuant to a series of treaties concluded under the League of Nations’ auspices to protect national minorities who are, in a sense, living in a state other than the state of their ethnicity or nationality or language.

And then, in the 1980s, there were a series of notable cases, beginning with Bosnia Herzegovina initiating proceedings against Serbia under the Genocide Convention. There was a case subsequently in 2008, whereby Georgia brought proceedings against Russia in respect of alleged ethnic cleansing in the enclave of South Ossetia. So there were periodic cases where States that were directly injured were using the legitimacy, authority, and visibility of the court as a platform, for what some would call ‘lawfare’ (using international law as the continuation of politics by other means), trying to isolate and pressure states who are responsible for human rights violations.

But in recent times, there has been a return to the actio popularis litigation, which really was, for some time, limited to the South West Africa case that I mentioned from the 1960s. One notable case was the proceedings by Belgium against Senegal, under the Convention against Torture, invoking the extradite or prosecute provisions of the convention in respect of Hissène Habré, the former dictator of Chad, who was residing in Senegal, and although that was actio popularis litigation, the Belgian judiciary had initiated proceedings against this individual. So there was some sort of connection with Belgium.

But the turning point, perhaps, was the Gambia vs. Myanmar in 2019, when the small West African nation of Gambia brought a case really on behalf of the members of the Islamic Organization for Cooperation, who were concerned by the persecution and ethnic cleansing against the Rohingya Muslim minority in Myanmar. That was really the first genuinely actio popularis proceeding since Southwest Africa, and it was met with success, at least at the provisional measure stage, with a 17 to 0 order issued by the court against Myanmar. Following the successful example of the Gambia versus Myanmar case, Canada and the Netherlands initiated proceedings against the Syrian Arab Republic under the Convention against Torture and subsequent to the Israel-Hamas conflict, South Africa initiated what is perhaps to date the most controversial case before the court, initiating proceedings against Israel under the Genocide Convention. That was followed by Nicaragua, initiating proceedings against Germany, also under the Genocide Convention, in respect of Germany's support for Israel.

And, as you put it, now a coalition of 4 countries, led by Germany, together with Canada, Australia, and the Netherlands, has signaled that it may initiate proceedings against the unrecognized Taliban leadership in Afghanistan under the Convention on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women.

So there is now really a steady stream approximating a flood of cases before the court in which you have what one could call altruistic litigation in the sense that the states are not directly injured. But it's never truly altruistic, because there is always a political interest which explains the motivations of states in invoking the moral authority of the ICJ as an extension really of their foreign policy, and therein lies both the distinction between a human rights court, where individuals can initiate proceedings, if they are directly the victim, as opposed to interstate proceedings, where States will invariably be selective and have their own interest.

So this proliferation of so-called public interest litigation, on the one hand, is welcome because it has made the ICJ and international law more relevant than ever, not just in our elite academic and practitioner circles, but even in the eyes of the public. Many people who would never have heard of the ICJ are now aware of its existence at least. But the problem is that reducing human rights litigation to interstate proceedings, which is invariably selective and politicized, also risks entangling the court in highly controversial disputes, in a manner which may not necessarily increase its legitimacy in the eyes of the world.

So I would say that this historical juncture, where there is unprecedented recourse to the court, is also an opportunity for us to pause and consider why so many years after the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, do we still not have a UN human rights court?

And is it time to rethink the very weak and fractured mechanisms that currently exist at the UN Level for the enforcement of human rights to have a more robust, consolidated jurisdiction that could disentangle itself from this sort of politicization.

KG: What about the relationship between the ICJ and the International Criminal Court? Do you see ways that they are complementary or ways that they overlap, and may be confusing or problematic?

PA: Well, the main distinction is that the jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court is focused on the attribution of individual criminal liability, whereas the ICJ jurisdiction extends to disputes between states. That is the main distinction. But of course, there will be overlap where, for example, the ICC and ICJ will be considering the same matter.

This occurred in a different context when Bosnia brought the Genocide Convention proceedings against Serbia, and then subsequently Croatia brought proceedings against Serbia, also under the Genocide Convention. And in parallel to the ICJ proceedings, there was the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, the ICTY, which was an ad hoc jurisdiction, established in 1993, 5 years prior to the establishment of the ICC. The ICJ gave great weight and relied very heavily on the findings of fact and law made by the ICTY, and one could say the same thing in respect of the ICC. That the ICJ, if it addresses, let's say, a certain conflict in which there are allegations of genocide, for example, under the Genocide Convention, the ICJ may look to the jurisprudence or findings of the ICC. In that regard, in particular, the evidentiary threshold for ICC proceedings is much higher than that before the ICJ. Because they involve finding guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, as opposed to state responsibility, which generally would have a balance of probabilities approach, even if it is heightened in the context of serious allegations, such as the crime of genocide.

So, for the most part, this raises the issue of the unification and harmonization of international law between different jurisdictions, which are not in a hierarchical relationship. This is not a case where a judgment of the Ontario Court of Appeals, for example, is brought before the Supreme Court of Canada, which can, in effect, overrule the lower courts. You have the ICJ, you have the ICC, and you have a number of other jurisdictions, none of which are in a hierarchical relationship with each other. So it falls on these jurisdictions to do their utmost, where possible, to avoid what's called the fragmentation of international law, where different jurisdictions come to opposing conclusions on the same set of facts applying the same laws. And that is why I think that it is always in the back of the mind of judges to try, where possible, to adopt consistent findings, whether of fact or law.

KG: You have been centrally involved in the case that Gambia has brought against Myanmar under the Genocide Convention, alleging that the Myanmar government is responsible for genocide against the Rohingya. To readers, it may not be necessarily obvious as to why a small West African country was the one to initiate that case. Could you give us an overview of how that case came to be?

PA: It's a good question. And as I mentioned, the issue of the Rohingya, the ethnic cleansing by the Myanmar military forces against the Rohingya Muslim minority, was an important matter for the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, which has 57 members extending from Africa and the Middle East to Southeast Asia. And, the question of why the Gambia, specifically, it's in part because Gambia had at that time a newly elected democratic government, after many years of a notorious dictatorship, and the Minister of Justice of that government, Abubacarr Tambadou, was previously a prosecutor at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, and perhaps had a certain understanding of the importance of international courts and tribunals in addressing such issues. In a visit to the Rohingya refugee camps in Bangladesh, on the border of Myanmar, he was especially affected by the stories of the survivors. So that was at least part of the story, that there was an individual with influence in a government who believed that it was important to speak truth to power, and not to be indifferent to such a grave injustice.

But at the same time, one could also say that the Gambia had very little to lose. It didn't really have extensive diplomatic or economic, or other relations with Myanmar, and therefore, it had very little to lose. As distinct, for example, from Bangladesh, which is neighbouring Myanmar, which is hosting some one million Rohingya refugees, and which has to negotiate regularly with its neighbour, and to try and maintain good, at least peaceful relations. So, sometimes the state that has the least to lose is the ideal applicant in bringing such proceedings.

KG: What do you think we can expect of an eventual ICJ ruling in that case?

PA: Well, I'm not going to speculate on what the court will eventually decide. There is a significant volume of evidence before the court, and it will be up to the 17 judges of the court to assess the evidence in light of the applicable law and come to their own conclusions.

And of course, one of the problems is that the ICJ, unlike a national court, does not have general jurisdiction; one cannot presume jurisdiction, because the foundation for international law, whether in respect of which norms are binding or which courts have jurisdiction, the foundation is state consent. States must consent to be brought before a particular jurisdiction, not in this specific instance, but they must have signed a treaty or made a declaration which recognizes the jurisdiction of the court. Now, under Article 36, paragraph 2 of the ICJ Statute, there is what is called the optional clause declaration, where a state can declare that it recognizes the jurisdiction of the court in general. And that's ideal for a state that has made a reciprocal declaration because it allows for proceedings in respect of all matters of international law. But when a state such as Myanmar has not made such a declaration, then one must search for another basis for jurisdiction. And that basis for jurisdiction was Article IX of the 1948 Genocide Convention, which allows States to bring disputes regarding the Genocide Convention before the court.

So the court's jurisdiction in this instance is limited to allegations of genocide. Allegations of war crimes or crimes against humanity cannot be brought before the court because the court has no jurisdiction. So it creates an artificial situation where the applicant state has to shoehorn its claim into the crime of genocide, because it's genocide, or it's nothing. You cannot say that “Well, there are also war crimes and crimes against humanity.” The court will simply say, we have no jurisdiction.

So this creates, you know, a distortion in the way in which human rights issues are brought before the court. And that's yet another reason why we need a proper human rights court rather than one which has this fragmented and piecemeal basis for jurisdiction.

KG: Moving on, you have also closely followed the case at the ICJ, which the Netherlands and Canada have brought against Syria under the Convention against Torture. How significant is this case? And do the clearly very significant political changes in Syria impact those proceedings?

PA: I, together with my distinguished colleague Alex Neve, had proposed such a case, and lobbied for it as early as 2016, but unfortunately there was no willingness at that point to initiate such a case. And the reason why the idea of going to the ICJ was important is that the ICC had no jurisdiction in respect of Syria. These horrific crimes are being committed in the context of a civil war which had erupted in 2011. I think it was France that, on two occasions, submitted a resolution whereby the UN Security Council to refer Syria to the ICC. And this is the only way in which the ICC can exercise jurisdiction against a non-state party. This basis for jurisdiction was invoked for the first time in 2005 against Sudan, for the atrocities being committed in the Darfur region, and in 2011 against Libya, when the Gaddafi regime was brutally suppressing the revolutionary uprising.

So in 2014, with the Russian Federation and China vetoing the referral of Syria to the ICC, it became very clear that the only other jurisdiction that one could invoke was the ICJ, even if it was not addressing individual criminal responsibility.

So it took quite a few years, I believe, until 2020, before the Netherlands, perhaps inspired by the example of the extraordinary visibility of the Gambia versus Myanmar case – which was helped by the presence in court of Aung San Suu Kyi, the Nobel Prize Laureate and human rights champion who disappointingly had decided to become the agent and an apologist, in effect, for the atrocities being committed against the Rohingya – which created massive interest in the global media.

So perhaps inspired by that example, the Netherlands, which was subsequently joined by Canada, decided to reawaken this earlier proposal to bring proceedings against Syria, except that, as important as it was, it was quite a few years after the worst atrocities had already been committed, and it was difficult, perhaps, to persuade the court that there was an element of urgency, because in bringing provisional measures—which is the way you get before the court quickly, rather than having to wait several years until a final hearing of the merits—it's necessary to establish urgency in the threat of irreparable harm.

Now, what's interesting is that Syria, of course, did not show up, unlike Myanmar, and that always diminishes the impact of the case. But it is still possible to continue the proceedings without the specific consent of a respondent, so long as there's a basis for jurisdiction which there was here in the compromissory clause of the Convention against Torture. And what is remarkable is that just as Canada and the Netherlands were busy preparing the memorial for this case, the main written pleading where they set up their case, the Assad regime was overthrown. And now there is an entirely new leadership. So that will have a significant impact on the case. The new leadership obviously does not wish to shield those in the Assad regime who are responsible for torture and other international crimes. Assad himself has fled now to Moscow, so he would have to be extradited in order to be brought to justice.

There are other Assad officials, some of whom have fled, others of whom may be in hiding, others of whom were, for the most part, executed by angry mobs. So the question now is, how to leverage the ICJ proceedings, perhaps to persuade the new leadership to put in place some sort of transitional justice policy, and mechanism, and it remains to be seen whether that will be feasible or not.

KG: Onto the final question: Do you see possibilities to deepen and expand the types of human rights cases being brought before the ICJ?

PA: Well, it's always possible for there to be more proceedings, actio popularis, and other proceedings. There is no shortage, tragically, of situations in the world that call for this sort of intervention.

I think that there is now a momentary setback for the international legal order in particular, with the commencement of the second Trump Administration. There is a clear signal that the rule-oriented international order will be subordinated to power politics for the most part, and a disregard, if not dismantling, of multilateralism in general, including a diminishing of the power of international organizations, such as the United Nations.

So in this climate, and against that backdrop now already of an unprecedented volume of cases having been brought before the court, it remains to be seen whether there will be an expansion and deepening, or whether there will be a lull, if you like, for some time, where states busy themselves with more immediate concerns. And I say this because, as we know, there is really no direct means of enforcement in respect of ICJ, or, for that matter, ICC decisions. Their power is derived largely from the power of legitimacy, or what Professor Tom Frank famously called the “compliance pull of international law.”

At the end of the day the reason why we have something called international law is because, to quote famous words of Professor Oscar Schachter, “most nations obey most laws most of the time.”

So there is a process of socialization, if you like, and internalization of international norms. And in the context of global interdependence, where military might and economic power have to be mediated through legitimacy, through persuasion, international law plays a very important role. So ultimately because we don't have formal enforcement mechanisms, much of the power and relevance of international law is a culture which is receptive to the idea that in a diverse world, with differing civilizations and cultures and political systems and competing national interests, there must be a transcendent universal set of norms, through which nations are able to converse with each other, to deal with each other, other than through bullying and intimidation, and the idea of “might makes right.”

And of course this isn't just a naive ideal. It is born of centuries of war and bloodshed that the international community finally came to the conclusion that it must establish the United Nations. It must adopt the UN Charter, it must prohibit recourse to wars of aggression. It must respect human rights.

So I think that for now we have a detour, perhaps, towards an earlier period of anarchy, “might makes right,” this whole idea of “America First,” the Russian aggression against Ukraine, the whole host of other centrifugal forces which, frankly speaking, are on the wrong side of history.

And it's important to say this, this is not just a question of morality, but it's also a question of what the course of history is. The course of history has been irresistibly pushing us towards ever greater and inextricable interdependence. And when you have a highly interdependent system, it also becomes very vulnerable and in need of cooperation, in need of norms that allow this system to function. So in that sense, I would also say that—and returning back to the theme of litigation before the courts—one of the most notable recent developments has been the climate change advisory proceedings before ITLOS, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea and the International Court of Justice.

And I had the privilege of representing the Commission of Small Island States on Climate Change and International Law, so-called COSIS, and it is remarkable that the smallest of nations on earth—including one of my clients, Tuvalu, population 11,000 Indigenous Pacific islanders—have initiated these proceedings. Because ultimately, one can say that climate change is perhaps the biggest human rights issue of our time. In the sense that we can decide to ignore a genocide in this or that corner of the world because it doesn't affect us, but we cannot choose to remain indifferent to climate change because it is truly inescapable. It is going to affect all of us.

So, a group of small island states initiated unprecedented proceedings before ITLOS and the ICJ in the context of advisory proceedings. So there is not a specific respondent state, but it is asking the question as to whether international law has anything to say about catastrophic climate change. And in that context we begin to see that there is a scientific truth that we are confronted with when we are dealing with climate change and the Paris Agreement of 2015, based on the uncontested scientific evidence detailed in reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which acknowledges that to avert the worst catastrophic harms from climate change, we must keep temperature rises within 1.5°C above pre-industrial temperatures by the year 2100.

That threshold, unfortunately, was breached last year in 2024. And perhaps the horrific fires in Southern California, were the opening chapter of the post-1.5°C world. And the science tells us that with every incremental rise in temperature after 1.5°C, there is an exponential increase in catastrophic harm.

Now I speak about scientific truth in the sense that scientists are not ideologues. They're not on the political left or political right. They just make measurements, and they tell us what's going to happen if we don't reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

But at the same time one sees among the Indigenous Pacific Islanders that I've dealt with, that ancient wisdom also is as compelling as modern science, and as the Attorney General of one of the small Pacific Island States, Vanuatu, who said before the court, “If you respect nature, nature will respect you.”

So, why do I say this? Here we have a remarkable cluster of human rights issues. We have the rights of Indigenous Peoples to self-determination, which, in the case of the small Pacific islands is being threatened in an existential sense, because rising sea levels will swallow these islands, and they will be under the sea within a generation. And at the same time, one sees that what is happening to the Pacific Islanders today in terms of the right to life, the right to security, will also affect the rest of us tomorrow, and these small islands are like the canary in the coal mine of a climate disaster.

So this brings me back to the future of international human rights law before international courts and tribunals. International courts and tribunals don't exist in a vacuum, they reflect a certain historical, cultural, and civilizational reality born of painful experience. It was the Holocaust and total war that in 1945 resulted in or gave birth to the Charter of the United Nations. And today, I would say that climate change is arguably the biggest threat to our collective survival as humankind inhabiting a common planet. And to the extent that world leaders are calling this a hoax, or are otherwise diminishing its importance to serve the interests of the fossil fuel industry, or what have you, then we are going to pay a catastrophic price. Because nature has its own laws, and the Earth will go on with or without us.

And in that sense I'm optimistic that even if today’s powerful states, the major polluters, are ignoring international law, are ignoring the jurisprudence of courts in respect of the harm, the principle of transboundary harm—which basically states that a state cannot conduct activities on its territory that causes significant harm to other states–which has obvious application in the context of climate change. Sooner or later we will be left with no choice but to return with a vengeance to an even stronger rule-oriented international order. Because in effect, climate change, migration, trade, human rights, one could go on and on: virtually every significant human activity today has a global dimension. And if we do not accept that reality and create global institutions that are necessary for solving those problems, then we will pay the price and, in that sense, I think we should not despair too much about this momentary retreat in international law. We should move forward with even greater faith and determination to create global justice, to create a world based on law rather than naked power. And we should have confidence that history is on the side of those who have that vision for our future.

KG: Thank you so much for your time and for sharing these thoughtful and timely insights, Professor Akhavan.

________________________________________

Citation: Kathleen Gant, “An Interview with Payam Akhavan” in Human Rights and the International Court of Justice — Challenges and Opportunities : a special issue of the PKI Global Justice Journal (2025) 9 PKI Global Justice Journal 5.

About the Authors:

Professor Payam Akhavan is an international human rights lawyer. He is the inaugural holder of the Massey Chair in Human Rights at the University of Toronto’s Massey College and was previously a Full Professor in the Faculty of Law at McGill University. He is a Member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague. He is a former Special Advisor on Genocide to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court and previously served as a Legal Advisor to the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Professor Akhavan has published extensively on human rights and international criminal law in leading academic journals and is on the Editorial Review Board of Human Rights Quarterly.

Professor Payam Akhavan is an international human rights lawyer. He is the inaugural holder of the Massey Chair in Human Rights at the University of Toronto’s Massey College and was previously a Full Professor in the Faculty of Law at McGill University. He is a Member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague. He is a former Special Advisor on Genocide to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court and previously served as a Legal Advisor to the Office of the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia. Professor Akhavan has published extensively on human rights and international criminal law in leading academic journals and is on the Editorial Review Board of Human Rights Quarterly.

Kathleen Gant is a third year Queen’s Law student, and a Carleton Bachelor of Humanities alumni. Throughout her law degree Kathleen has been Co-President of Outlaw and the Mental Health and Disability Club. She has also participated in the Clara Barton International Humanitarian Law Competition, where her team won Best Application, and the Kawaskimhon Moot.

izzuanroslan | shutterstock.com

Courts in Conversation: The International Criminal Court, the International Court of Justice and their mutual and respective roles in Addressing International Crimes

by Mark Kersten

Courts in Conversation: The International Criminal Court, the International Court of Justice and their mutual and respective roles in Addressing International Crimes

Introduction

In recent years, several wars and mass atrocity events have come under the scrutiny of not just one international court, but two. Situations like Russia’s war in Ukraine, Israel’s ongoing war in Gaza and occupation of Palestinian territories, atrocities against the Rohingya people of Myanmar, as well as the Taliban’s persecution of women and girls, have fallen under the purview of both the International Criminal Court (ICC) and International Court of Justice (ICJ). Observers of international law are accustomed to these Hague-based institutions being confused for each other in media portrayals. This confusion is unlikely to abate given the increasing overlaps between the atrocity events that have come under each court’s jurisdiction.

Few have attempted to articulate the consequences of this new dynamic or the relative strengths and weaknesses of each institution as venues to address the perpetration of international crimes, let alone their potential to work constructively and together to deliver a proverbial one-two punch of accountability for mass atrocities. With both institutions coming under increasing strain and with each susceptible to wider attacks on whatever remains of a rules-based order, such an assessment seems timely and is therefore the focus of this essay.

Before proceeding, it is important to briefly lay out the similarities and differences between the ICC and ICJ. Both are international courts based in The Hague, The Netherlands. However, the ICJ is an organ of the United Nations and deals exclusively with disputes between states. Created in 1945, the ICJ’s ambit is wide—much wider than international crimes. It covers, inter alia, territorial and boundary disputes between states, the lawfulness of certain kinds of nuclear weapons tests, reparations owed between states over breaches of international laws and, most recently, the obligations of states to address climate change. The ICJ can be asked to issue both advisory opinions, which carry legal authority but are not binding on states or, in so-called contentious cases, it can issue binding opinions in disputes where states accept to be bound to its rulings. Sometimes referred to as the “World Court,” the ICJ deals with state responsibilities and therefore instructs state, rather than individual, behaviour.

While the ICC has a relationship with the United Nations and may, in some cases, be asked to investigate situations of mass atrocities by the UN Security Council, it is an independent body and institution established by its member-states. It is created by the acceptance of states of its founding treaty, the 1998 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. Established in 2002, the ICC is mandated to investigate and prosecute core international crimes—war crimes, crimes against humanity, genocide, and the crime of aggression—in the territories of states that have acceded to the Rome Statute and by citizens of its member-states. It can also investigate in situations referred to it by the Security Council and in states that have voluntarily accepted the jurisdiction over the Court. The ICC has 125 member-states and has numerous ongoing investigations occurring in situations such as Ukraine, Palestine, Georgia, Libya, Darfur, the Philippines, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Central African Republic, and Afghanistan. It has prosecuted numerous individuals, including both state- and non-state actors. The ICC can only investigate and prosecute individuals and is therefore exclusively focused on individual criminal responsibility for the core international crimes under its jurisdiction.

While the key difference between the ICC and ICJ is their respective emphasis on individual versus state responsibility, one can nevertheless appreciate that such legal differences are not always apparent to certain constituencies. While the legal distinction between state and individual responsibility is clear, some will inevitably view the pursuit of individual responsibility for international crimes against government and state leaders as implicating the state itself, and judgements against certain states for violations of international law as implicating individual state leaders. For this reason, and even more so because both the ICC and ICJ are engaged in determining unlawful conduct in relation to the same situations of mass atrocities, a richer understanding of the relative strengths and weaknesses of these institutions’ engagement in this area is of use to scholars, advocates, diplomats, and policymakers.

Overlapping courts

As noted above, the overlaps between the ICC and ICJ include contexts where international crimes and serious breaches of international law have been committed: Ukraine, Palestine, Myanmar, and Afghanistan. Additional overlaps may be forthcoming in contexts like Azerbaijan’s expulsion of the Armenian population of the Nagorno-Karabakh enclave. Put simply, there are and will continue to be situations where both courts exercise their jurisdiction at the same time. The overlap between courts examining both state and individual responsibility is not entirely new, with atrocities committed in the Balkans during the 1990s also triggering cases under international criminal law, at the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), as well as the ICJ. However, measured by the number of situations under consideration by the ICC and ICJ, the intensity of these overlaps has grown in recent years. This suggests that advocates of international law, many of whom work on both public international law before the ICJ and international criminal law matters before the ICC, may not see an unenterable firewall between what the ICJ does and what the ICC does. Indeed, why not double down and seek to address both state and individual responsibility for international crimes like genocide (as in the cases of Ukraine, Palestine and Myanmar) and such severe forms of discrimination against women and girls that it may amount to gender persecution (as with the Afghan cases)? After all, the perpetration of these kinds of atrocities requires both individual perpetrators as well as that of the state.

Amidst expanding overlaps, certain trends stick out. One is that allegations of genocidal violence have been far more common in ICJ cases than at the ICC. Indeed, in none of the above situations—Ukraine, Myanmar, or Palestine—has the ICC pursued charges of genocide against individual perpetrators, although investigations into each context are ongoing and we cannot prejudge their outcomes. In general, the ICC has been reluctant to prosecute genocide, issuing only one arrest warrant in relation to the crime, for former Sudanese President Omar al-Bashir who was likewise charged by the Court with war crimes and crimes against humanity.

What remains to be seen is whether the ICC and ICJ enter into any form of constructive dialogue in relation to overlapping subject matter. If, for example, the ICJ eventually comes to a determination that Israel or Russia have committed genocide in Gaza, Myanmar, or Ukraine, will that compel the ICC into issuing warrants for the likes of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Russian President Vladimir Putin, or Burmese Acting President Min Aung Hlaing on allegations of genocidal conduct? If so, would the ICC rely on findings of the ICJ in doing so?

It seems probable that affirmative findings by the ICJ would place significant pressure on the ICC. Indeed, it would be odd if the ICJ determined that a state bore responsibility for violations of the 1948 Genocide Convention yet the ICC declined to act against individuals responsible for planning and perpetrating genocide. A more likely situation would be what transpired over genocidal violence committed by the Serbian army in Srebrenica in 1995; both the ICJ and the ICTY addressed the genocide, the former finding the Serbian state responsible for failing to prevent genocide and the latter in relation to the individual responsibility of perpetrators over genocide, including senior Serbian officials Radko Mladic and Radovan Karadžić. A notable determination of the ICJ’s case was also that it found Serbia had wrongfully failed to cooperate with the ICTY in punishing the individuals who committed the genocide. Similar findings seem likely in future cases relating to breaches of the Genocide Convention where the ICC has concurrent jurisdiction.

The growing coincidence of the ICC and ICJ over the same conduct underlying mass atrocities raises questions about the very relationship between state responsibility and individual responsibility. As suggested, if a state is found to be liable for genocide, it should follow that individuals are liable too. After all, and to paraphrase the famous judgement of the 1946 Nuremberg Tribunal, it is men and not the abstract entity of states that commit crimes against international law.

The costs and benefits of ICC and ICJ addressing international crimes

Insofar as cases at the ICJ and investigations conducted by the ICC coincide, it is helpful to assess their relative strengths and weaknesses. In what follows, I do so in relation to three parameters: (i) their ability to galvanize state support and engagement; (ii) their ability to withstand political interference; and (iii) the enforcement of their decisions. The analysis is far from exhaustive and does not touch on some key issues (such as the selectivity in cases before each institution). However, I hope it can represent an overture for a more sustained dialogue about the role of these courts against the backdrop of unrelenting attacks on the international rule of law.

(i) Galvanizing state engagement and support

Both the ICJ and ICC appear to have galvanized collective engagement and support (as well as their share of opposition) for their work in responding to atrocity crimes. This is evidenced by the coalitions that have either instigated or offered compelling support for specific cases. Such engagement and support have had significant symbolic and legal impacts, as evidenced by the following examples.

Prior to the 24 February 2022 invasion of Ukraine by Russia, the ICC had jurisdiction in Ukraine despite it not being a member-state of the Court, because of Kyiv’s decision to voluntarily submit itself to the jurisdiction over the ICC under Article 12(3) of the Rome Statute. A limiting factor in the scope of the ICC’s jurisdiction, however, was that the Prosecutor would require the approval of judges of the Pre-Trial Chamber to open an official investigation into the situation in Ukraine, a potentially cumbersome process. That changed on 2 March 2022, when thirty-nine states jointly referred Ukraine to the ICC. An official investigation into international crimes committed in Ukraine was commenced that very day. Since then, multiple arrest warrants have been issued for Russian authorities, most notably against President Vladimir Putin on charges of the war crime of forcibly transferring children from Ukraine into Russia and Russian-held territory.

The ICC’s work on the situation in Palestine also enjoyed multilateral state support when, on 17 November 2023, Bangladesh, Bolivia, Venezuela, Comoros and Djibouti jointly referred the situation in Palestine to the Court. Unlike in Ukraine, this joint referral was a largely symbolic demonstration of support for the ICC; the Prosecutor had already opened an investigation in 2021, prior to the atrocities committed on 7 October 2023 and in its wake.

In the context of the ICJ, states have also come together in support of its cases. The case at the ICJ over the alleged commission genocide against the Rohingya people by Myanmar was brought by The Gambia. However, it is important to note that Banjul brought the case with the full backing of the fifty-seven member-Organization of Islamic States. In addition, seven states - Maldives, Canada, Denmark, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK – have joined the case against Myanmar as intervenors.

The ICJ’s case over the legal consequences of Israel’s illegal occupation of Palestinian territories likewise received the support of many states. Indeed, the case was brought to the ICJ as a result of 98 United Nations member-states requesting the Court’s opinion on the occupation via a UN General Assembly resolution. In the proceedings against Russia over its alleged breaches of the Genocide Convention in Ukraine, some two-dozen states have filed to intervene alongside Ukraine.

Of course, the express support of states for certain cases before the ICJ and investigations by the ICC does not invariably translate into support for specific outcomes. Moreover, some cases, particularly those relating to atrocities committed in Palestine, continue to generate opposition from certain quarters, most loudly from the United States. There are thus varying levels of support and engagement across certain cases and contexts, illustrative of geopolitical differences, tensions, and divergent commitments to the international rule of law. This is certain to continue, and it remains an open question as to whether differences in opinions among states will promote or fracture commitments to the courts’ work and whether they will remediate or exacerbate double standards in the application of international law.

(ii) Withstanding political interference and pressure

An important attribute of international courts is their capacity for resilience and therefore their ability to weather political storms instigated by state responses to their jurisdiction over politically sensitive subjects, such as genocide and war crimes allegations. On this count, both courts thus far appear robust, albeit with one facing far graver threats than the other. The ICC has had to prove its ability to resist concerted attempts to undermine it by states, and faces an unprecedented, even existential, campaign of political coercion from the United States, one that the Court’s President has said may “jeopardise its very existence.”

As its workload touches on the geopolitical interests of powerful states, particularly the United States, Israel, and Russia, the ICC has faced repeated attempts to interfere with its work. In 2023, it faced a serious cyberattack (almost certainly the doing of Moscow), one that has cost it millions of dollars to address. In 2024, repeated and long-standing attempts by the Israeli intelligence service Mossad to threaten and coerce ICC staff were revealed by journalists. And in 2025, the Trump administration took aim at the Court, passing legislation that would permit it to sanction not only ICC staff, but the institution itself.

To date, the Court has survived these attempts to interfere with its operations and mandate. It has continued its work undeterred, and even secured the arrest of former President of the Philippines Rodrigo Duterte over charges of crimes against humanity, a remarkable achievement for an embattled institution. Nevertheless, whether the ICC can withstand ongoing pressures and attacks on its operations and survive in its current configuration remains an open question, especially as conducting its work undeterred by external threats may lock the institution into a cycle of escalation with the United States.

Despite operating in the same theatres, including in Ukraine and Palestine, the ICJ appears to have been largely impervious to similar attempts to interrupt and interfere with its work. This may be in part because the vast majority of states accept its jurisdiction and typically choose to engage directly with the Court, even when facing serious charges relating to genocide and other international crimes. Of note here, both Myanmar and Israel participated in proceedings at the ICJ in relation to violations of the Genocide Convention (although Israel did not participate in proceedings related to the legal consequences arising from its unlawful occupation of Palestinian territories).

However, as the ICJ engages more regularly in questions of genocide, implicating and frustrating the perceived interests of major powers like the United States (via its ally in Israel) and Russia, it may very well come under increased scrutiny and even attack. Recent years and even more recent developments have taught advocates of international law that it is foolhardy to take hard-fought gains reflected in the post-WWII and post-Cold War rules-based order for granted.

(iii) Enforcement of decisions