September 22, 2020

Special Tribunal for Lebanon and telecommunications evidence

By: James Hendry

The Trial Chamber of the Special Tribunal for Lebanon released its judgment in the case of Prosecutor v. Salim Jamil Ayyash, Hassan Habib Merhi, Hussein Hassan Oneissi and Assad Hassan Sabra on August 18, 2020. (A fifth conspirator Mustafa Amine Badreddine died during the proceedings and will be included in this article in the collective ‘accused’). The Tribunal found Ayyash guilty under the Statute of the Special Tribunal for Lebanon and the Lebanese Criminal Code of conspiracy of committing a terrorist act, committing a terrorist act by means of an explosive device, intentional homicide of the former Prime Minister of Lebanon Rafik Harari with premeditation by using explosive materials, intentional homicide of 21 other individuals with premeditation using an explosive materials and attempted intentional homicide of a further 226 individuals with premeditation by using explosive materials. Charges were dismissed against the others. The full judgment runs 2682 pages while an authentic authoritative summary was released composed of salient extracts of the judgment. Paragraph numbers refer to the summary, the primary source for this article, unless otherwise identified. This article will focus on the Office of the Prosecutor’s (OTP’s) extraordinary use of telecommunications evidence from mobile phones - that did not include the content of the calls - to prove the charges. There was little other evidence offered by the OTP.

The context of the crimes has been set out in an earlier article in this Journal https://globaljustice.queenslaw.ca/news/special-court-for-lebanon-conviction-for-terrorism. The charges against the accused were based on their participation in the death by triggered by a suicide bomber of Harari, his entourage, those in proximity to his motorcade and serious injury to hundreds of people who had the misfortune of being close to the blast.

Circumstantial evidence

The burden of proof on the OTP was to prove the charges beyond a reasonable doubt. The telecommunications evidence against the accused was circumstantial. It contained no evidence of the substance of meetings between the accused and the other individuals involved, nor any content of the myriad of mobile telephone conversations that formed the bulk of the evidence against the accused. There were no intercepts nor texts nor voice mails.

Thus, the OTP had to build its case based on inferences from the evidence which had to meet the test for probity of circumstantial evidence. The inferences alleged by the OTP had to be the only reasonable explanation from the evidence.

The sources and types of telecommunications data

The telecommunications evidence was composed of the business records of two major Lebanese telecommunications providers: Alfa and Touch. They provided:

• cell site data records describing technical information about each cell tower in the providers’ system including the cell tower’s ID, its specific location and technical data about its field of coverage that could be used to identify which cell tower was activated by any given mobile phone at any specific time. The OTP tendered expert evidence on ‘cell site analysis’ which is a forensic technique used to identify the approximate location of the user of a mobile phone based on the cell tower to which the phone connects during a call (full judgment, para. 371), and

• call data records which provided information about the source and destination telephone numbers, the date and time of the call, its duration, the identity of the actual mobile handset used and the cell tower to which the mobile connected.

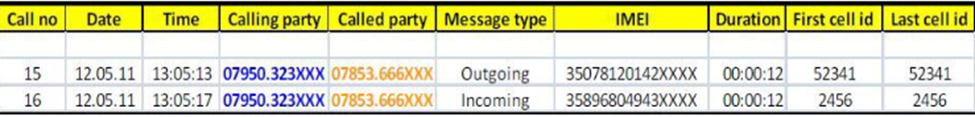

There were billions of call data records in evidence, so both OTP and Defence agreed to admit ‘call sequence tables’ recording the chronology of calls relating to a specific phone number over a time period. These looked like the schematic below illustrating a call between two mobiles on the same day:

(para. 52, as taken from the Philips’ expert report in evidence called “An introduction to cell site analysis as applied to GSM records.” One can imagine the thousands of entries in a call sequence table for two mobiles over the many months of surveillance and the execution of the attack.

The Trial Chamber was satisfied that the telecommunications experts called by the OTP were sufficiently reliable to assess the general locations and movements of the mobiles attributed to the accused (para. 109). Their opinion was based on call data records and cell site data showing the cell towers to which the attributed mobiles most likely connected (there was no GPS evidence).

The OTP used software to show this relative movement of attributed mobiles and patterns of their activities in court.

The Trial Chamber said that it was bound to assess the totality of the relevant evidence to determine whether sufficiently definite patterns would emerge that were so striking to be beyond coincidence and therefore meet the criminal standard of proof. Ultimately, this meant patterns that largely presented themselves from matching the information in the call sequence tables with the movements of identifiable users. The patterns would have to form successively larger patterns to tie the accused to the various elements of the crimes charged.

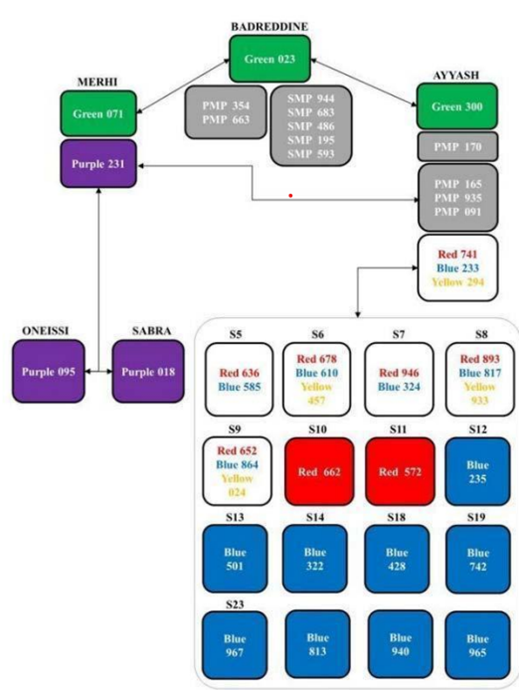

The search for patterns started with the OTP alleging that the accused carried out the Harari assassination by using groups of mobiles operating as networks each with a high frequency of calls within it. The OTP assigned colours to each network. The OTP alleged that three Green mobiles formed a network that coordinated the attack and a false claim of responsibility for it to divert attention form the accused. Eight Red mobiles formed a network to carry out the attack. Fifteen Blue mobiles and thirteen Yellow formed networks to prepare for the attack and carry out long term surveillance of Harari. Three Purple mobiles would coordinate the creation of a diversionary claim of liability so the attack would be attributed to a fictitious group.

The first pattern: networked mobiles

The Trial Chamber heard evidence about how these coloured networks were identified. Lebanese security forces requested of the telecommunications companies provide them with the identities of all mobiles on all networks providing the best cell tower coverage at the crime scene. Next, they asked the companies for a list of calls from each of these mobiles over time to identify possible suspects (para. 2149, full judgment).

Next, the Trial Chamber heard expert evidence of “mission phone” or “covert networks” created usually for “nefarious” purposes and for the anonymity of its members. The OTP experts testified that a wide range of factors can establish that a group of mobiles operated as a network: the setup of the network, its equipment, mobile usage and activity and how the network ends its operation (paras. 2153-6, full judgment).

The “covert networks”

The OTP argued that the alleged crimes were carried out based on expert evidence that five coloured “covert networks” were operating with mobiles that maintained their user’s anonymity. There was a high frequency of calls within each network. The OTP alleged that three Green network mobiles, identified as part of the group by their SIM cards, monitored preparations for the attack. One of the Green phones and the Purple phones were alleged in a complex operation to publicise a false claim of responsibility for the attack. Further, the OTP alleged that the users of eight Red network mobiles coordinated the attack. Another, fifteen Blue network and thirteen Yellow network mobiles primarily carried out months of surveillance of Harari before the attack. The OTP alleged that the schematic below showed who was using the various personal and network phones (para. 120).

The Trial Chamber decided that the telecommunications data had sufficient probative value to prove that specified mobiles were communicating with each other in each network as well as their approximate location and movements (paras. 110-3). It also decided that the accused were using the mobile phones attributed to them (though not all mobile users could be identified). Thus, the telecommunication evidence could be relied on to determine whether the personal mobiles of accused Ayyash, Badreddine and Merhi were co-locating with the relevant network mobiles and that these mobiles had a single user.

The Trial Chamber relied on similar factors for each alleged network to conclude that at least some of the suspect mobiles (three Green, eight Red, six Blue, four Yellow mobiles) were each part of a covert network:

• the proximity of the date, sequence and seller of the SIM cards,

• the use of fake ID or none at all to purchase them

• proximity of when and where they were activated and first used,

• proximity of payment for them and the use of cash

• exclusivity of calls between the mobiles in the network

• the anonymity of users and the lack of text messaging, voice mail, call forwarding or night use

• similarity in place and times of use, especially if they corresponded with Harari’s movements

• the abrupt and apparently co-ordinated termination of their use.

The Trial Chamber held that Three Green, eight Red, six Blue and four Yellow network mobiles formed covert networks that were interconnected and coordinated and operated that way until the date of the attack (Yellow stopped earlier). The call sequence tables established that the users of the three Purple mobiles were the personal phones of Oneissi, Merhi and a phone that was attributed to Sabra, and that these users must have known each other, based on the number of calls between them ending on the day of the attack.

The pattern in co-locating of personal and covert network mobile phones

The Trial Chamber then had to determine whether the OTP had proved that the mobiles used within the networks were used by the accused during the relevant period. This required co-location of personal mobiles with network mobiles based on patterns of cell tower connection showing that they were being used at the same time.

The OTP had to overcome the problem that the accused did not subscribe to the mobile service(s) they used in their own names. Nor was there evidence of the content of the calls. The OTP had to identify patterns of mobiles used in suspect networks that appeared connected to the surveillance or the attack on Harari, to identify personal mobiles that co-located with the suspect networked mobiles and finally to identify the users of those co-located mobiles based on patterns of their use by themselves and in relation to each other over a period of time.

The Trial Chamber then made findings on evidence of the use of personal phones and their co-location with the covert network mobiles.

It found that Ayyesh used his residential landline 696 from April 2003 to October 2007 and his residential landline 851 from September 2004 to December 2005. It was satisfied that he used mobile 165 contacting family and business associates from April 2002 to April 2004 which was proved by activation of cell masts around his residences and office. He used mobile 170 from January 7 to November 2005. He used mobile 935 from May 2004 to January 2005, largely based on its use in a car accident in November 2004, handset use, contact and geographic profiles. He was the user of mobile 091 from January 13, 2005 to March 2005. The SIM cards for 935 and 091 were used on the same handsets from January 13, 2005. The Trial Chamber found expert evidence that 091 and 170 co-located ‘particularly convincing’ which pointed to co-location with Green 300 and thence to Red 741 which had a lead role in the attack (paras. 185, 213, 215 and 217).

Additionally, the Trial Chamber found that the OTP had established use of Yellow 669 by Ayyesh only on a balance of probabilities based on common movement and cell tower activations. However, it held that the number of co-locations of 935 and Yellow 294 based on calling and location patterns proved beyond a reasonable doubt that he was the principal user of Yellow 294 from August 2004 to January 13, 2005. The Trial Chamber also found that 170 and Blue 233 had a single user and that the same person used 091 and Blue 233, based on the numbers of co-locations from call-pairings determined by their triggering the same cell towers within a short period, leading to the conclusion that Ayyash was the user of Blue 233 from January 10 to February 14, 2005. Having found Ayyash to be the user of 935, 091 and 170 and covert network mobiles Yellow 294 and Blue 233, the Trial Chamber found that the number of possible co-locations between these mobiles and their common movements over four and one-half months led to the conclusion that Ayyash was also Green 300’s user from September 30, 2004 to February 14, 2005. The Trial Chamber was also satisfied that Red 741’s possible co-locations shown by cell tower activations and common movement proved that Green 300 and Red 741 had the same user. Possible co-locations with the other personal and networked mobiles proved Ayyash to be the user of Red 741 from January 14 to February 14, 2005 – a vital point in his prosecution. The Trial Chamber also rejected evidence that Ayyesh went to Saudi Arabia for the Hajj in January 2005, a fact, if proved, would have prevented inferences of his use of mobile phones during that period.

The Trial Chamber was satisfied that Mehri’s family mobile 6091 co-located with Purple 231, a mobile alleged to have been linked to the attack by its alleged involvement with the false claim of liability. The Mehri Defence called evidence of another mobile designated the “Grey” mobile supposedly to prove there was another user of Green 071 to increase the doubt he was part of that network alleged to have monitored and coordinated the attack. However, the Trial Chamber held that the Grey mobile was used solely by Mehri (para. 231). The OTP then tried to prove Purple 231 and the Grey mobile co-located with Green 071, but the Trial Chamber held there was an inadequate number of calls and lack of movement traced through the cell towers to conclude Green 071 was co-locating with Purple 231 or the “Grey” mobile so as to prove Mehri was the single user of the three phones (paras. 242-3). The Trial Chamber could not find the Purple network connected Mehri, Oneissi or Sabra to the attack (para. 428).

The Trial Chamber held that Oneissi was the principal user of Purple 095. As with the rest of the Purple network, no call pattern was established that linked it to the conspiracy.

The Trial Chamber was satisfied that mobiles 546 and 657 had the same user as the SIM cards sequentially used in the same handset and that Sabra first used Purple 018 as a family phone before also using 546 and later 657 (para. 257). However, the Trial Chamber could not find that Sabra was its sole user based on geographic and contact profiles. There was no evidence of it being used as a contact.

The Trial Chamber held that personal mobiles 354, 663 and 944 that co-located with Green 023 was used by Badraddine as sole user (para. 276). There was direct evidence that he used 354 and 663 which had overlapping geographic profiles, use patterns and common contacts. He also used 944. 354 and 944 co-located and 944 and 633 co-located. All three co-located for 57 days between September 2004 and February 12, 2005, moving consistently. However, he died in 2016. Evidence of his role played a role in the framework of the analysis of the attack.

Tracking the phones’ movements

The Trial Chamber concluded that evidence of cell tower connection was sufficiently probative to discern patterns of cell connections to conclude that surveillance was occurring. Patterns of calls, cell tower activations, mobile movements and Harari’s movements were important in determining that these elements were related (para. 294). As already noted, there was no direct evidence of network mobiles’ surveillance of Harari. However, surveillance was vital to the attack because of the sophistication of his security measures (including electronic jamming equipment on the vehicles) requiring technical information on his movements and habits as well as those of his security detail. There was circumstantial evidence of calls between the network mobiles and patterns of co-location of the relevant mobile cell tower activations with Harari’s travel routes.

On the issue of surveillance, the Trial Chamber had to work backwards from the day of the attack and examine cell tower activations and calls and corelate them with Harari’s locations. There was ample evidence of Harari’s movements from staff and others involved with his activities. The Trial Chamber noted that triggering of a cell tower only proved a general area of where a mobile was when in use, limiting its probative effect. Cell tower overlap in central areas of a city such as Beirut added further uncertainty.

The Trial Chamber held that the role of the Red network in the assassination was “obvious” based on the number and location of the calls between them, the significant number of calls before the attack, the immediate termination of the Red network before the attack and the speedy location and relocation of the mobiles along the route.

Using the evidence

In the end, the Trial Chamber agreed that the evidence led to one conclusion: that the networked mobiles were largely engaged in surveillance of Harari up until the attack (paras. 296, 301). The networked mobiles were indeed shadowing Harari as evidenced by the sequence of cell tower activations near his security team, ceasing when Harari was out of Lebanon. There was no other reasonable conclusion inferable from this circumstantial evidence.

Thus, the OTP proposed that the Trial Chambers should infer from the co-location of personal phones of the accused with covert networked phones, that they clearly formed networks with a role in the attack on Harari. Certainty of co-location of a personal phone with one of these covert networked phones allowed the expert witnesses to co-locate the networked phones with aspects of the conspiracy. These aspects included mapping network surveillance activity based on the records of the travel routes used by Harari around Lebanon for months before the final attack and the coordination of the calls of networked phones and their movements on the day of the attack.

Without evidence of the content of the calls, the Trial Chamber could not determine whether there was a hierarchy with the Green network on top as alleged by the OTP: it was not the only reasonable inference that could be drawn from the mass of data.

The Trial Chamber could not conclude from the evidence of the activity or location of the personal phones that constituted the Purple network in the afternoon of the attack that Merhi, Oneissi or Sabra were involved in making the false claim of responsibility that might have tied them to the crimes. Further, the cell service was severely disrupted by the attack making it unreliable.

Proving the crimes

After providing its analysis of the legal elements of the crimes and modes of liability as discussed at length by Joseph Rikhof in https://globaljustice.queenslaw.ca/news/special-court-for-lebanon-conviction-for-terrorism, the Trial Chamber went on to make specific findings on these elements.

First, the Trial Chamber held that the explosion was a terrorist act under article 314 of the Lebanese Criminal Code. Direct evidence and logic showed that the combination of the size of the explosion, the manner and location of its detonation, the fact the target who was a prominent politician in Lebanon and the fact the attack was detonated by a suicide bomber would all work together to generate public terror.

The Trial Chamber also held that the objective elements of intentional and attempted intentional homicide were established.

The Trial Chamber held on the charge of conspiracy to commit a terrorist act that the only inference reasonably drawn from the totality of the evidence is there must have been an agreement (conspiracy) between two or more people to commit a terrorist act by means of an explosive device to kill Harari (para. 455). However, though covert mobile network activity showed that, while many people were involved in the surveillance of Harari, the purchase of the suicide truck, the attack, and the attempt to make a false claim of responsibility afterwards, the Trial Chamber was handicapped in its assessment of guilt by the lack of content of the phone conversations – or other, direct evidence - that might prove who were knowingly involved (para. 488). The result was that though logically, many persons were involved in the conspiracy, it was impossible to prove they all had the necessary knowledge to make them liable for their part in the conspiracy. There were too many explanations for the location of the various networked mobiles to meet the “only reasonable explanation for the available circumstantial evidence” test.

The exception was the driver of the suicide truck who detonated the explosive (para. 460).

The Trial Chamber then found all six Red mobile users were part of the conspiracy as an “assassination team” because of their surveillance of Harari before the attack, the significant number of calls between them, the times and places of their calls on the day of the attack and the simultaneous cessation of activity just before the attack occurred. Their activity suggested that each Red user knew before the attack that its aim was to kill Harari by explosive device in a public place (paras. 504-506, 550). These actions also proved the Red mobile users contributed to the execution of the crime satisfying the actus reus for co-perpetration of intentional homicide (para. 552).

The Trial Chamber postulated that the more extensive contact a mobile user had with other mobiles and with the acts needed to prepare for the terrorist attack, the more likely it was that he knew its aim. Ayyash fit this profile as user of Red 741. His use of this mobile was the sole evidence connecting him with the explosion (para. 543). The Trial Chamber held that the only reasonable explanation for the evidence of his call activity on this mobile made it inconceivable that he did not know of the aim. His calls to the other Red mobiles triggered the relocation of those other Red mobiles to the Parliament area just before the attack and so must have started the operation in motion. His uniquely extensive contact with the all the other Red mobiles on the day of the attack supported an inference that he coordinated at least some of the acts in the attack. The Trial Chamber held this was the only reasonable explanation of the totality of the evidence and proved his part in the conspiracy beyond a reasonable doubt. The Trial Chamber held that the final decision to execute the attack occurred only a couple of weeks before and so this must have been the time period in which Ayyash agreed to join the conspiracy (paras. 519, 521). He also co-perpetrated the intentional homicide of Harari by his central and leading role in the attack (paras. 552). He also co-perpetrated the attempted intentional homicide of members of Harari’s convoy and the public (para. 559). The Trial Chamber held that the evidence supporting all charges was the same, including the mens rea for all counts (para. 548). Ayyash was found guilty on all counts.

The Trial Chamber found that the absence of context for calls between Mehri, Oneissi and Sabra based on the failed false claim of liability could not connect them to the conspiracy.

The Trial Chamber held that the high volume of calls made by mobiles in the Green network back and forth to Badreddine did not prove that he was the main conspirator as alleged by the OTP. The calls were not related to each other sequentially nor to the events surrounding the attack (para. 536). The Trial Chamber was not satisfied that the Green network was in command. There were voluminous calls between the networks and there was a clear sequencing of calls, passing on information up and down the networks. But without evidence of the content of the calls, the Trial Chamber was not satisfied of a hierarchy among networks (para. 539).

Conclusion

It is rare that a case of this importance rests on evidence that is devoid of content. This case has been going on for fifteen years and has involved forensic experts from many countries with many different skills. But the evidence was gathered from the co-location of personal and covert networked mobile phones and patterns of movement of individuals who committed a heinous crime tracked by the activation of cell towers that transmitted short untraceable messages between phones. Even the concept of covert networks that were established to allow anonymous but linked calling patterns was the product of evidence given by experts who could distinguish between networks established for evil purposes and those that might simply be a group of friends who communicated frequently. Yet patterns of mobile phone use, their sequence showing the transmission of information between phones at certain times and places were sufficient to enable the Trial Chamber to determine the only reasonable explanation for circumstantial evidence on issues of actus reus and mens rea for the serious crimes in this case.

This article could be cited as James Hendry, “Special Tribunal for Lebanon and telecommunications evidence” (2020), 4 PKI Global Justice Journal 34.

About the author

James Hendry is a Co-Editor-in-Chief of the PKI Global Justice Journal. He served as counsel to the Canadian Human Rights Commission before joining the Department of Justice in 1989. He was General Counsel in the Human Rights Law Section at the DOJ until retirement in 2011, working in civil Charter social policy review, specializing in equality rights, human rights legislation, and human rights act design. He has also published extensively on Canadian and comparative constitutional issues and has lectured in Canada, Spain, South Africa, the United States and Hong Kong.

James Hendry is a Co-Editor-in-Chief of the PKI Global Justice Journal. He served as counsel to the Canadian Human Rights Commission before joining the Department of Justice in 1989. He was General Counsel in the Human Rights Law Section at the DOJ until retirement in 2011, working in civil Charter social policy review, specializing in equality rights, human rights legislation, and human rights act design. He has also published extensively on Canadian and comparative constitutional issues and has lectured in Canada, Spain, South Africa, the United States and Hong Kong.